The First World War (1914–1918) not only changed the course of history but also transformed the nature and purpose of poetry. It inspired profound poetry, evoking the atmosphere and landscape of battle perhaps more vividly than ever before. The First World War poets – many of whom lost their lives – became a collective voice, illuminating not only the war’s tragedies and their irreparable effects but also the hopes and disappointments of an entire generation.

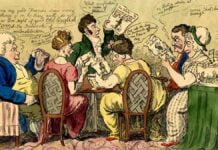

Before the war, poetry often glorified heroism, patriotism, and the beauty of sacrifice. But as the war progressed and the horrors of modern mechanised warfare became clear, poets began to question traditional ideals and depict the brutal reality of conflict.

The poetry of the First World War represents one of the most powerful literary responses to human suffering, loss, and disillusionment. It charts a movement from patriotic enthusiasm to bitterness, pity, and protest, reflecting the evolution of public sentiment during the war years.

Early War Poetry: Patriotism and Idealism

At the outbreak of war in 1914, many poets responded with patriotic fervour. They saw the war as a noble cause — a test of courage, honour, and sacrifice for one’s country. The tone was romantic and idealistic, drawing upon earlier traditions of martial and pastoral poetry.

Key Features

- Idealisation of duty, heroism, and sacrifice.

- Romantic imagery of soldiers as noble warriors.

- Propagandist tone encouraging enlistment and patriotism.

Notable Poets and Works

Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

His sonnets, especially The Soldier, express serene acceptance of death for England.

“If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.”

Brooke’s poetry reflects innocence and purity of intent rather than experience. He died early in the war, before witnessing the front-line horrors that later poets would describe.

The Trench Poets: Realism and Disillusionment

As the war dragged on and trench warfare brought immense suffering, the tone of poetry shifted dramatically. The poets who experienced the front — known as the Trench Poets — wrote of mud, blood, fear, and futility. They replaced the earlier romanticism with stark realism, irony, and compassion.

Themes and Features

- The gruesome reality of life in the trenches.

- The loss of innocence and moral questioning of war.

- Anger at political hypocrisy and empty patriotism.

- Emphasis on comradeship, pity, and the dehumanising effects of war.

- Use of vivid imagery, colloquial language, and irony.

Notable Poets and Examples

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

The most influential of all war poets, Owen described war as “the pity of war.“ His poems combine graphic realism with deep compassion.

Dulce et Decorum Est exposes the falsehood of the old Latin motto (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”) by describing a gas attack.

“If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs…”

Anthem for Doomed Youth laments the death of soldiers, likening their deaths to slaughtered cattle:

“What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?”

Owen’s poetry humanises the soldier’s suffering while condemning blind nationalism.

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967)

A soldier-poet like Owen, Sassoon combined satire and protest. In works such as The General and Base Details, he attacked the incompetence of military leaders and the hypocrisy of those who glorified war from a distance.

“If I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath,

I’d live with scarlet Majors at the Base.”

His directness and irony broke from the decorum of traditional verse, creating a new voice of protest.

Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

A painter and poet of working-class background, Rosenberg’s work, such as Break of Day in the Trenches, combines striking imagery and philosophical reflection.

“Poppies whose roots are in man’s veins

Drop, and are ever dropping.”

Rosenberg’s poems blend realism with a surreal awareness of nature’s indifference to human suffering.

Ivor Gurney (1890–1937)

Gurney’s poetry expresses both his love of the English countryside and his trauma as a soldier. In To His Love, he mourns a fallen comrade with quiet pathos.

Thematic Transformation: From Glory to Pity

The transition in war poetry mirrors the psychological and moral journey of an entire generation. What began as a patriotic adventure turned into a tragic confrontation with death, fear, and futility.

Major Thematic Developments

- Loss of Innocence: The war shattered the optimistic faith in human progress that had characterised the Edwardian era.

- Pity and Compassion: The soldier became a victim rather than a hero. Owen’s phrase “the pity of war“ captures this humanistic focus.

- Nature and Irony: Nature, once idealised, becomes indifferent or hostile. The pastoral landscapes of Brooke give way to the desolate wastelands of Owen and Rosenberg.

- Critique of Authority: Poets like Sassoon directly challenged generals, politicians, and patriotic propaganda.

- Religious and Existential Doubt: Many poets questioned God, morality, and the purpose of human life in the face of senseless destruction.

Women’s Voices in War Poetry

Though men dominated the front lines, women poets also offered powerful perspectives. Their poetry explored grief, waiting, loss, and the social roles forced upon them by war.

- Vera Brittain (1893–1970): In Perhaps and her memoir Testament of Youth, she writes of personal loss and the futility of war.

- May Wedderburn Cannan and Margaret Postgate Cole expressed disillusionment with patriotic rhetoric and empathy for the dead and wounded.

Women’s poetry provided an alternative voice — compassionate, domestic, and critical — broadening the emotional and moral scope of war literature.

Post-war Reflection and Legacy

After 1918, the war poets profoundly influenced both literature and public consciousness. Their works redefined war poetry as an act of truth-telling and memorialisation rather than celebration.

Post-war Developments

- The publication of The Oxford Book of Modern Verse (1936) by W B Yeats included many war poets, though Yeats controversially excluded Owen.

- The 1920s and 1930s saw war poetry become central to modernist explorations of disillusionment and alienation.

- Later wars (World War II, Vietnam, Iraq) saw poets return to the First World War poets as models for expressing trauma and protest.

Cultural impact

The imagery of mud, trenches, poppies, and gas masks became part of the collective memory of war. The phrase “Lest we forget“ captures how poetry keeps that memory alive.

The Poppy as Symbol

The red poppy, popularised by Canadian poet John McCrae’s poem In Flanders Fields, became a universal symbol of remembrance.

“In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row.”

The image of poppies growing among soldiers’ graves symbolises both beauty and blood — life persisting amid destruction. It remains one of the most enduring emblems of World War remembrance.

Style and Technique

War poets introduced a new realism and emotional honesty to English poetry.

- Direct, plain diction replacing ornate Victorian style.

- Use of irony and bitter contrast.

- Vivid, sensory imagery of mud, blood, and gas.

- Broken rhythms and half-rhymes to reflect disorientation.

- Juxtaposition of natural imagery with mechanical warfare.

This stylistic transformation helped pave the way for modernist poetry, influencing writers such as T S Eliot and W H Auden.

The Human Legacy

The First World War poets gave voice to an entire generation’s trauma. They humanised the soldier, exposing war’s psychological wounds long before “shell shock“ was fully understood. Their work reminds readers that war is not glorious, but tragic — not noble, but wasteful.

As Wilfred Owen wrote in his preface to his poems:

“My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.”

This statement became the moral foundation of twentieth-century war poetry — poetry that bears witness, condemns injustice, and keeps memory alive.

Poetry of the First World War represents a monumental shift in both form and feeling. From patriotic sonnets to anti-war elegies, it charts the collapse of old certainties and the emergence of modern sensibility. These poets — Owen, Sassoon, Rosenberg, Gurney, and others — turned personal suffering into collective remembrance. Their legacy endures not only as a record of history but as a timeless testament to the human spirit confronting the inhumanity of war.