Cubism was one of the most ground-breaking and influential art movements of the 20th century. Emerging in France between 1907 and 1914, it was developed chiefly by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who challenged traditional artistic conventions that had dominated since the Renaissance, particularly the rules of linear perspective, modelling, and illusionistic depth. Rather than portraying subjects from a single fixed angle, Cubist artists sought to represent multiple perspectives simultaneously, capturing the essence of objects through the use of abstraction, fragmentation, and reassembly. Instead of painting objects and people realistically, they broke them down into geometric shapes—such as cubes, squares, and triangles—and showed multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

Despite its eventual status as one of the most significant movements in abstract art, Cubism began under a cloud of derision. The term originated from a disparaging remark made by French art critic Louis Vauxcelles, who referred to the emerging style as nothing more than “little cubes,” expressing his disdain for what he saw as a radical departure from the realism and perspective of traditional painting. It was the French critic Guillaume Apollinaire who later adopted the term “Cubism” (Cubisme in French) in a more affirmative context. Rather than rejecting Vauxcelles’s label, Apollinaire embraced it, becoming one of the earliest and most influential advocates of the movement.

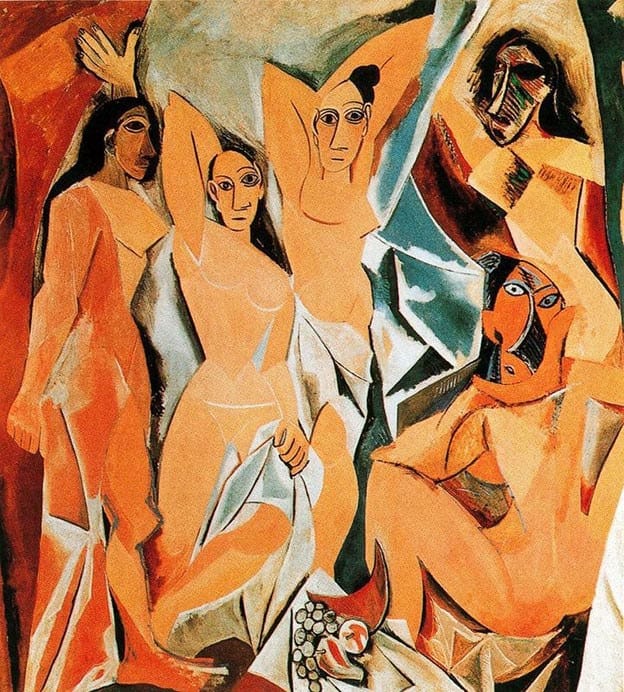

While influenced by earlier innovators such as Georges Seurat, Picasso introduced a radical departure from traditional representation by incorporating multiple perspectives through the use of flattened, geometric forms. His seminal work Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), depicting a group of women rendered in angular and fragmented forms, is widely regarded as the first Cubist painting. Picasso collaborated closely with Georges Braque, and it is now broadly accepted that the two artists jointly developed the foundational principles of Cubism. Although the movement originated in France — as reflected in the French title of Picasso’s painting — it quickly gained international significance. Not all of the early Cubists were French nationals; many, including Picasso himself, a Spaniard, were foreigners living and working in France, contributing to a cross-cultural artistic exchange that would profoundly influence the trajectory of 20th-century art.

A group of artists formed an intellectual and artistic circle known as the Puteaux Group, convening in the Puteaux suburb of Paris to explore and discuss emerging developments in modern art, with a particular focus on the evolving Cubist style pioneered by Picasso. The group included Jean Metzinger, Marie Laurencin, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier, and Albert Gleizes, though neither Picasso nor Georges Braque were members. Their absence should not be interpreted as exclusion, as it reflects the broader reality that artists often engage with movements through different channels. Picasso was known to be on friendly terms with members of the group —he exhibited alongside Laurencin, with whom he formed a close personal and professional connection.

The Puteaux Group’s joint exhibition at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in October 1911 marked a significant moment in the history of modern art, presenting the first public showcase of Cubist work. The group maintained strong ties with the influential Apollinaire, who had played a key role in popularising the term ‘Cubism’ and who supported their efforts to define and disseminate the movement’s visual language. In 1912, their subsequent exhibition introduced a broader collective under a new name: Section d’Or (The Golden Section). This title was a deliberate reference to the golden ratio, a mathematical proportion often associated with harmony and aesthetic balance in both nature and art. It signalled their intent to explore the geometric and intellectual dimensions of Cubism, and possibly to differentiate their approach from the more narrowly focused experimentation of Picasso and Braque.

Visual Characteristics

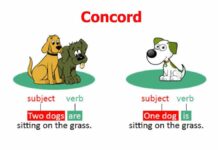

Cubism is characterised by its reduction of forms into geometric components and its depiction of subjects from multiple viewpoints within a single frame. The paintings often lack a clear distinction between foreground and background, emphasising a structural flatness that disrupts traditional perspective. Contrary to pure abstraction, Cubism aims to capture a heightened form of realism—a reflection of how we perceive the world not as static, but through shifting and overlapping perspectives.

Geometric Simplification

Natural forms were reduced to cubes, spheres, cones, and cylinders. Objects were simplified into sharp angles and flat planes.

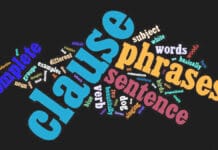

Multiple Perspectives

Objects were presented from various angles simultaneously, creating a dynamic and nonlinear perspective. Artists often depicted different aspects of an object in a single painting (e.g., a face might show both the front and side simultaneously).

Flattened Picture Plane

Depth was collapsed; background and foreground merged.

Neutral Colours

Early Cubist works used mostly browns, greys, and blacks instead of bright colours. Emphasis was placed on structure over colour.

Collage Elements

Later, artists like Picasso incorporated real-world materials (such as newspaper and fabric) into their paintings. Integration of text, materials, and found objects.

Phases of Cubism

Analytical Cubism (1907–1912)

- Complex, fragmented shapes (almost like shattered glass).

- E.g., Portrait of Ambroise Vollard by Picasso.

This early phase, exemplified in works like Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Braque’s Violin and Palette, focused on breaking down objects into their basic geometric components. Artists used a limited, often monochromatic palette (greys, browns, ochres) to avoid distracting from the form and structure. The compositions appear dense, with interlocking planes and complex spatial arrangements, giving viewers a sense of intellectual deconstruction of the subject.

Synthetic Cubism (1912–1914 and beyond)

- Simpler shapes and brighter colours.

- Used mixed media (collage).

- E.g., Still Life with Chair Caning by Picasso.

In this later phase, artists began to rebuild rather than analyse forms, introducing collage elements such as newspaper clippings, wallpaper, and fabric into their paintings. This brought new textures, colours, and meanings into art. Synthetic Cubism is more decorative and often easier to read than Analytical Cubism, as seen in Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning. It marked the beginning of the incorporation of everyday materials into fine art, a practice that would influence Dada and Pop Art.

Key Artists and Influences

- Pablo Picasso (Guernica, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon)

- Georges Braque (Violin and Candlestick)

- Juan Gris (The Sunblind)

While Picasso and Braque are credited as the founders, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Albert Gleizes, and Jean Metzinger were also prominent Cubist artists. Juan Gris, in particular, contributed a more systematic and ordered approach to Cubism, often with clearer forms and vibrant colours. Cubism was influenced by Paul Cézanne, whose late work emphasised basic geometric forms and challenged traditional perspectives, and by African tribal art, which inspired Picasso’s mask-like faces and angular stylisation.

Cubism not only transformed painting and sculpture but also had a profound impact on architecture, design, film, and literature. In literature, its fragmented approach inspired modernist writers like James Joyce and Gertrude Stein, who experimented with syntax, time, and narrative structure. Cubism laid the groundwork for Futurism, Constructivism, De Stijl, and even Bauhaus design principles. It opened the door to abstraction and conceptual art, emphasising the idea and form over representation.

Cubism broke the rules of traditional art, inspiring later movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism. It made people think differently about reality and perspective. Cubism represented a radical rethinking of visual representation, transforming the viewer from a passive observer into an active interpreter. By dismantling the traditional illusion of space and form, it forced a new way of seeing—one rooted in intellectual engagement, geometric innovation, and a modern understanding of reality as fragmented, shifting, and constructed. It remains a cornerstone of contemporary art, celebrated not only for its aesthetic achievements but for its profound theoretical and cultural influence.