Feminism is a broad intellectual, political, and social movement advocating for the rights of women on the grounds of equality of the sexes. It challenges gender-based inequalities in law, culture, education, employment, and personal life, aiming to dismantle patriarchal systems that privilege men. Although often regarded as a modern movement, feminist ideas have existed for centuries, evolving across various historical contexts and geographical regions.

Historical Development of Feminism

Early Roots

While not referred to as “feminism” at the time, the seeds of feminist thought can be found in ancient texts (E.g., Plato’s Republic, which suggests that women could be guardians) and medieval challenges to traditional gender roles. Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) is often seen as an early feminist text.

First Wave (19th – early 20th century)

Focus: Legal and political rights, particularly the right to vote (suffrage).

Key Figures: Mary Wollstonecraft (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792); suffragists like Emmeline Pankhurst in Britain and Susan B Anthony in the United States.

Achievements: Women’s suffrage in many Western countries, reforms in property and marital laws.

Second Wave (1960s – 1980s)

Focus: Expanding equality to social, cultural, and economic spheres. Addressed reproductive rights, workplace discrimination, domestic violence, and sexuality.

Key Figures: Simone de Beauvoir (The Second Sex, 1949); Betty Friedan (The Feminine Mystique, 1963); Gloria Steinem and the women’s liberation movement.

Achievements: Legalisation of contraception and abortion in many countries, anti-discrimination laws, and greater access to education and employment.

Third Wave (1990s – 2000s)

Focus: Diversity and intersectionality, challenging the idea of a single “female experience.” Emphasised race, class, sexuality, and global perspectives.

Key Figures: Bell Hooks (Ain’t I a Woman?), Judith Butler (Gender Performativity), Chandra Talpade Mohanty (Postcolonial Feminism).

Achievements: Recognition of multiple identities, LGBTQ+ inclusion, critiques of mainstream (“white, middle-class”) feminism.

Fourth Wave (2010s – present)

Focus: Digital activism, intersectionality, body positivity, MeToo movement, reproductive justice, and transgender rights.

Characteristics: Social media campaigns, global solidarity, emphasis on dismantling systemic sexism and gender-based violence.

Branches and Theoretical Approaches

Liberal Feminism

Liberal feminism is rooted in the Enlightenment tradition of equality and individual rights. It argues that women should have the same opportunities as men in education, employment, politics, and law. Rather than seeking to overturn the entire system, liberal feminists focus on reforming existing institutions to ensure fairness. They campaign for equal pay, anti-discrimination legislation, and equal access to professions and political office. The central idea is that if laws and policies treat women equally, society will naturally move towards gender justice.

Radical Feminism

Radical feminists argue that patriarchy is not just a surface-level problem but the most profound and most pervasive form of oppression, shaping family life, sexuality, culture, and politics. They emphasise that gender inequality is systemic, woven into the very fabric of society. Radical feminists call for a complete restructuring of institutions, particularly those that perpetuate male dominance, such as traditional marriage, religion, and media. They also highlight issues like reproductive rights, sexual violence, and control over women’s bodies, stressing that liberation requires more than legal reform — it demands cultural and structural transformation.

Marxist/Socialist Feminism

Marxist and socialist feminists link women’s oppression to capitalism and the economic exploitation of labour. They argue that gender inequality cannot be separated from class inequality, as capitalism relies on women’s unpaid domestic work and their lower-paid labour in the workforce. According to this view, true gender equality can only be achieved by dismantling capitalist structures and ensuring collective ownership and redistribution of resources. Socialist feminists stress solidarity between gender and class struggles, pointing out how working-class women often face the harshest forms of exploitation.

Cultural Feminism

Cultural feminists believe that there are innate differences between men and women, often celebrating qualities traditionally associated with femininity, such as empathy, care, and creativity. Unlike radical feminism, which sees gender differences as socially constructed tools of oppression, cultural feminism sometimes interprets them as valuable and positive. Advocates argue that society should embrace and prioritise these qualities instead of marginalising them. The movement often creates women-centred spaces, art, and cultural practices, highlighting female creativity and spirituality.

Ecofeminism

Ecofeminism links the domination of women with the exploitation of nature. Ecofeminists argue that patriarchal systems treat both women and the environment as resources to be controlled and consumed. By drawing parallels between ecological destruction and gender oppression, they call for an ethic of care, sustainability, and harmony. Writers such as Vandana Shiva and Carolyn Merchant argue that reclaiming respect for nature is closely tied to empowering women, particularly in societies where women play a crucial role in managing natural resources.

Postcolonial Feminism

Postcolonial feminists critique Western feminism for often ignoring the voices and experiences of women in the Global South. They stress that issues such as colonialism, imperialism, and cultural identity are central to understanding women’s oppression worldwide. For instance, a woman in rural India may face different struggles — such as caste-based discrimination or lack of access to education — compared to a Western middle-class woman. Postcolonial feminists emphasise listening to diverse voices and avoiding a “one-size-fits-all” feminism dominated by Western perspectives.

Intersectional Feminism

Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality highlights how different forms of oppression — including race, class, sexuality, disability, and gender — intersect to create unique experiences of disadvantage. For example, the discrimination faced by a Black woman cannot be fully understood by looking at racism or sexism alone, but by recognising how the two combine. Intersectional feminism is now a cornerstone of contemporary feminist thought, ensuring that feminism addresses the diversity of women’s lives and resists privileging any single perspective.

Feminism and the Suffrage Movement

The suffrage movement was a central part of early feminism, particularly in Europe and North America. In the 19th century, women were generally denied political rights, barred from attending universities, restricted in their employment opportunities, and expected to remain in the domestic sphere. Reformers began to argue that this lack of political representation was unjust, as women paid taxes, worked, and contributed to society, yet had no say in how it was governed. Suffrage, the right to vote, became the key symbol of equality.

The British suffrage movement was one of the most influential. Early campaigners, such as Millicent Fawcett, led the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, which advocated for gradual reform through peaceful and legal means. Later, more militant activists, such as Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, who founded the Women’s Social and Political Union, employed protests, marches, and even acts of civil disobedience to draw attention to their cause. The slogan “Deeds, not words” reflected their frustration with the slow pace of progress. Suffragettes endured imprisonment, hunger strikes, and police violence, but their determination helped turn public opinion.

In the United States, leaders such as Susan B Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and later Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt, campaigned for women’s right to vote over the course of decades through petitions, speeches, and demonstrations. The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is often marked as the beginning of the organised movement in America, where the Declaration of Sentiments boldly declared that “all men and women are created equal.” After many setbacks, the movement succeeded with the passing of the 19th Amendment in 1920, granting American women the right to vote.

The suffrage movement wasn’t limited to Western countries. Across the world, women were mobilising for political rights. In New Zealand, women gained the vote as early as 1893, making it the first self-governing country to do so. In many other nations, suffrage came after long struggles tied to broader social and national liberation movements. For example, in India, women’s activism for suffrage was closely tied to the freedom struggle against British rule, where leaders like Sarojini Naidu effectively combined nationalist and feminist goals.

Feminism and the suffrage movement are deeply connected, but they are not identical. Suffrage was one specific aim, whereas feminism encompasses a wide range of issues, including domestic violence, equal pay, reproductive rights, and challenging gender stereotypes. Still, the fight for suffrage was a landmark moment—it proved that women could organise collectively, demand change, and achieve it, even against strong resistance. It also showed that political power is the foundation upon which other forms of equality can be built.

The legacy of the suffrage movement is profound. Today, when women vote and stand for office in most countries, it is easy to forget how radical and hard-fought that right once was. Feminism has since moved into new phases—addressing intersectionality, representation in media, LGBTQ+ rights, and global inequalities—but it owes much of its momentum to those early campaigners who fought for something as basic yet as powerful as the right to cast a vote.

Feminism in Literature

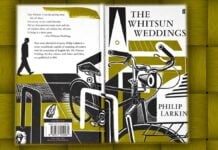

Feminist literature has played a vital role in exposing gender inequalities and creating alternative narratives. Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) laid early foundations by arguing for women’s education and intellectual equality. Later, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929) made a compelling case for women’s need for financial independence and private space to create literature. In the 20th and 21st centuries, writers such as Margaret Atwood (The Handmaid’s Tale), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (We Should All Be Feminists), and Arundhati Roy have explored issues of gender, identity, and power from diverse perspectives.

Feminism in Art

In the visual arts, feminist artists challenged the male-dominated art world. Frida Kahlo utilised self-portraits to reclaim female subjectivity, portraying her pain, identity, and political convictions. Judy Chicago’s installation The Dinner Party (1979) became an icon of feminist art, celebrating women’s history through symbolic place settings. Artists such as Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman utilised photography and visual texts to critique consumerism, beauty standards, and the objectification of women. Feminist art is not only about subject matter but also about questioning who makes art, how it is exhibited, and whose voices are represented.

Feminism in Film

Feminist film theory has exposed the ways in which women are represented in cinema. Laura Mulvey’s essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1975) introduced the concept of the “male gaze,” arguing that films often present women as passive objects of male desire rather than active subjects. Filmmakers like Agnès Varda, Chantal Akerman, and Jane Campion created films that resisted or subverted these conventions. Contemporary cinema increasingly explores feminist themes, from mainstream films like Little Women to experimental feminist documentaries and global women’s cinema.

Achievements of Feminism

Feminism has transformed laws, cultures, and everyday lives across the globe. The most significant achievements include the granting of suffrage rights to women in most countries, which was a central victory of the first wave of the women’s movement. In education and employment, feminist struggles opened doors for women to enter universities, professions, and leadership roles previously barred to them. Reproductive rights were another landmark, with access to contraception and abortion enabling women to control their own bodies and futures.

Feminism also exposed and fought against gender-based violence, leading to laws criminalising domestic abuse, marital rape, and workplace harassment. Campaigns such as MeToo continue this struggle, breaking the silence around sexual misconduct. Feminism also succeeded in shifting cultural attitudes — today, it is widely accepted that women can aspire to careers, political power, and personal independence, a radical departure from past centuries.

Criticisms of Feminism

Despite its achievements, feminism has faced criticism from within and outside. Some argue that early feminism primarily represented the concerns of white, middle-class women, neglecting the experiences of working-class women and women of colour. This issue has been addressed through intersectional and postcolonial approaches; however, tensions persist. Radical feminism has been criticised for alienating allies by portraying men collectively as oppressors, while liberal feminism is sometimes seen as too reformist, failing to challenge deeper structures of power.

In contemporary debates, disagreements over transgender inclusion in feminist spaces have also caused divisions. Critics from outside the movement often accuse feminism of undermining family structures, being “anti-men,” or promoting cultural division, though many feminists respond that their goal is justice, not reversal of oppression.

Global and Contemporary Dimensions

Feminism today is global in scope, addressing issues such as child marriage, access to education, honour-based violence, reproductive justice, and labour rights for women in developing countries. Campaigns like HeForShe, MeToo, and protests against femicide show feminism’s ongoing urgency.

Feminism is not a single, monolithic ideology but a diverse and evolving movement that has profoundly shaped modern society. From securing the vote to challenging the very categories of gender, it has continually adapted to new challenges. Its enduring significance lies in its demand for equality, justice, and dignity for all people, regardless of gender, and its insistence on questioning the social, cultural, and political structures that perpetuate inequality.