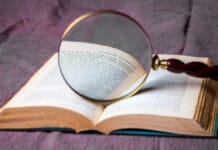

The second of Chomsky’s ‘three models for language description’ is Phrase Structure Grammar. A phrase structure grammar can generate any set of sentences that a finite state grammar can generate. But the converse does not hold: sets of sentences can be generated by a phrase structure grammar but not by a finite state grammar. To express the relationship between phrase-structure grammars and finite-state grammars, phrase-structure grammars are intrinsically more powerful than finite-state grammars (they can do everything that finite-state grammars can do- and more).

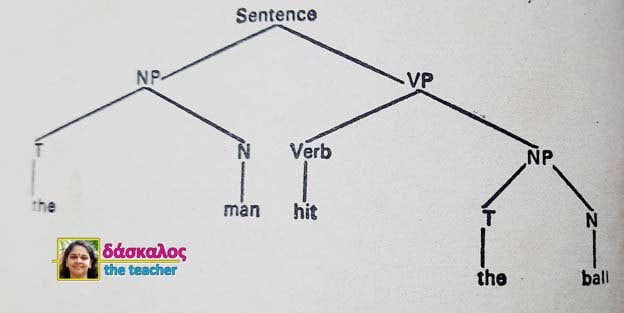

Consider the following English sentence: The man hit the ball. It comprises five words, and the sentence is composed of its ultimate constituents. The order in which the ultimate constituents occur relative to one another may be described as the linear structure of the sentence. A traditionally minded grammarian might say of our simple model sentence that it has a subject and a predicate, that the subject is a noun phrase(NP), which consists of the definite article(T) and a noun(N), and that the predicate is a verb phrase(VP), which consists of a verb(V) with its object, which, like the subject, is a noun phrase consisting of the definite article and a noun. Essentially the same kind of description would have been given by ‘Bloomfieldian’ linguists in terms of the notions of immediate constituent analysis: the ‘immediate constituents’ of the sentence (the two phrases into which it can be analysed at the first stage) are the noun phrase the man (which has the role, or function of the subject), and the verb phrase hit the ball (which has the function of the predicate); that the immediate constituents of the man are the article the and the noun man; that the immediate constituents of hit the ball are the verb hit and the noun phrase the ball (which has the function of the object); and that the immediate constituents of the ball are the article the and the noun ball.

The notion of constituent or phrase structure (to use Chomsky’s term) is comparable to bracketing in mathematics or symbolic logic. If we have an expression of the form x(y + z), we know that the operation of addition must be carried out first and the operation of multiplication afterwards. By contrast, x x y + z is interpreted (using the general convention that, in the absence of brackets, multiplication takes precedence over addition) as equivalent to (x x y) + z. Generally speaking, the order in which the operations are carried out will make a difference in the result. For instance, with x = 2, y = 3 and z = 5 : x x (y + z) = 16, whereas (x x y)+ z = 11. Many sequences of words in English and other languages are ambiguous in much the same way that x x y + z would be ambiguous if it were not for the prior adoption by mathematicians of the general convention that multiplication takes precedence over addition.

A classic example is the phrase old men and women (and more generally A N and N), which may be interpreted either as (old men) and women – (xy) + z or old (men and women) – x(y + z). With the phrase structure indicated, using brackets, as old (men and women), the string of words is semantically equivalent to (old men) and (old women) — x(y + z) = (xy) + (xz). The theoretical importance of this phenomenon lies in the ambiguity of such strings as old men and women, which cannot be accounted for by appealing to a difference in the meaning of any of the ultimate constituents or to a difference in a linear structure. Chomsky’s formalisation of phrase structure grammar may be illustrated using the following rules:

(1) Sentence- NP + VP

(2) NP- T + N

(3) VP – Verb + NP

(4) T – the

(5) N – {man, ball…}

(6) Verb – {hit, took…}

This set of rules, which will generate only a small fraction of English sentences, is a simple phrase structure grammar. Each rule is of form X -> Y, where X is a single element, and Y is a string of one or more elements. The terminal string generated by the rules is the + man+ hit + the + ball, and it takes nine steps to generate this string of words. The set of nine strings, including the initial string, the terminal string and seven intermediary strings, constitute a derivation of the sentence The man hit the ball in terms of this particular phrase structure grammar.

Operation of Rewriting

Whenever we apply a rule, we put brackets, as it were, around the string of elements that are introduced by the rule, and we label the string within the brackets as an instance of the element that the rule has rewritten. An alternative and equivalent means of representing the labelled bracketing assigned to strings of elements generated by a phrase structure grammar is a tree diagram. Since tree diagrams are visually more precise than sequences of symbols and brackets, they are more commonly used in the literature. The labelled bracketing, associated with a terminal string generated by a phrase structure, is called a phrase marker.

Chomsky’s revolutionary step, as far as linguistics is concerned, was to draw upon this branch of mathematics and apply it to natural languages, like English, rather than to the artificial languages constructed by logicians and computer scientists. But he did more than take over and adapt for the use of linguists an existing system of formalisation and a set of theorems proved by others. He made an independent and original contribution to studying formal systems from a purely mathematical point of view. The mathematical investigation of phrase structure grammar is now well advanced, and various degrees of equivalence have been proved, which also formalise the notion of bracketing or immediate constituent structure.