Imagism was a poetic movement that developed in the early 20th century, roughly between 1909 and 1917. It emerged as a reaction against the excesses of Victorian and Romantic poetry, which were often seen as verbose, sentimental, and ornamented. Imagist poets sought clarity, precision, and economy of language. At the heart of Imagism was the belief that poetry should present images directly, without unnecessary explanation, abstraction, or moralising. In practice, this meant using sharp visual or sensory impressions expressed in concise, carefully chosen words.

Core Principles of Imagism

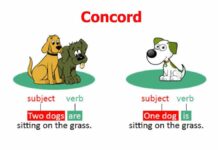

Direct Treatment of the Subject

The first principle of Imagism was the insistence on treating the subject matter directly, whether it was an object, a scene, or an emotion. Instead of building elaborate metaphors or philosophical reflections, the poet presented the subject with clarity, almost as if holding it up for the reader to see. Ezra Pound’s famous definition was “to use no word that does not contribute to the presentation.” For instance, in Pound’s short poem In a Station of the Metro, the faces of people in a crowd are directly compared to “petals on a wet, black bough” — simple, precise, and vivid.

Economy of Language

Imagists rejected wordiness. Every word in a poem had to earn its place. They avoided unnecessary adjectives, flourishes, or rhetorical embellishments. This principle made Imagist poetry often resemble Japanese haiku in its brevity and intensity. The goal was to create a distilled form of expression where the image itself communicated emotion, without explanatory commentary.

Use of Musical Rhythm Instead of Fixed Metrical Patterns

Rather than following traditional English verse forms such as iambic pentameter, Imagists advocated for free verse that echoed the natural rhythms of speech. This did not mean a lack of form or discipline; instead, it emphasised rhythm as organic, arising from the idea being expressed rather than imposed externally. This freedom allowed the imagery to flow with greater force and flexibility.

Clarity and Precision

Imagist poets insisted on clarity — choosing the exact word rather than a vague or decorative one. They avoided abstractions and generalisations, preferring concrete, sensory details. A chair, a flame, or a single gesture carried more weight than philosophical musings, because it was immediate and exact. This precision made Imagist poems short but powerful.

Key Figures

Ezra Pound

Often considered the founder of Imagism, Pound was instrumental in setting out its principles and editing early Imagist works. His short, crystalline poems, like In a Station of the Metro, epitomise the movement’s goals.

H D (Hilda Doolittle)

H D was one of the central poets of Imagism, producing spare, lyrical poems often inspired by classical themes. Her work conveyed a sense of beauty through simplicity and sharpness of image.

Amy Lowell

An American poet, Amy Lowell, became a strong advocate for Imagism after Pound moved on to other projects. She helped popularise the movement in the United States, editing anthologies of Imagist poetry and writing poems that exemplified its style.

Richard Aldington and Others

Other poets, including Aldington, Ford Madox Ford, and William Carlos Williams, contributed significantly to the Imagist project, each bringing individual nuances but united by the commitment to clarity, brevity, and imagery.

Influences on Imagism

Japanese Haiku and Chinese Poetry

One of the strongest influences on Imagism was the brevity and precision of Japanese haiku and Chinese classical poetry. These traditions demonstrated how much could be conveyed in a few words through vivid images. The Imagists adopted this model of suggestion and sharp focus.

Classical Models

Greek and Latin lyric poetry also influenced the Imagists, especially in its directness and concision. Pound and H D often looked back to these traditions for inspiration.

Modernist Context

Imagism developed alongside other modernist movements in art and literature, such as Cubism in painting and Futurism in literature. Like these movements, it broke away from tradition, emphasising innovation, fragmentation, and the search for new forms of expression.

Impact of Imagism

Revolution in Poetic Form

Imagism marked a radical break with Victorian and Georgian poetry. By abandoning traditional metre and rhyme schemes in favour of free verse and concentrated imagery, it opened the door to modern poetry as we know it today.

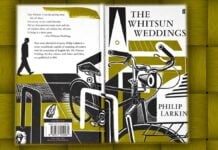

Influence on Later Poets

Imagism directly influenced modernist poets such as T S Eliot and Wallace Stevens, and it laid the groundwork for William Carlos Williams’ dictum “No ideas but in things.” Its emphasis on clarity and concreteness continues to shape contemporary poetry.

Anthologies and Publications

The Imagist Anthologies (1914–1917), edited by Pound and later by Amy Lowell, helped spread the movement’s principles to a broader audience. Although short-lived as a formal movement, Imagism had a long-lasting effect on 20th-century literature.

Example of Imagist Style

Ezra Pound’s In a Station of the Metro (1913):

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

In just two lines, Pound presents a powerful juxtaposition of an urban moment with a natural image. The economy of words, the clarity of imagery, and the musical rhythm without metrical regularity embody the essence of Imagism.

Criticism and Limitations

Critics have argued that Imagism, with its emphasis on the “pure image,” sometimes neglected broader social, political, or emotional contexts. Its poems could appear too brief, lacking depth or development. Furthermore, internal disagreements—especially between Pound and Lowell—fragmented the movement by the late 1910s. Yet, despite its short lifespan, Imagism permanently altered poetic style and expectations.

Imagism was more than a stylistic experiment; it was a foundational modernist movement that transformed the way poets thought about language, form, and meaning. By demanding precision, economy, and vividness, Imagists stripped poetry to its essentials and demonstrated that profound truths could be conveyed in just a handful of words. Though short-lived, its influence endures in contemporary poetry, which often privileges the concrete image over abstract elaboration.