The history and evolution of theatre is a rich and complex journey that reflects the cultural, spiritual, and political life of humanity across centuries. Originating in ritualistic practices and religious ceremonies, theatre has transformed from sacred performances in ancient temples and amphitheatres to a dynamic and multifaceted art form that embraces realism, experimentation, and activism. From the structured dramas of ancient Greece and the codified aesthetics of Sanskrit theatre to the moral pageants of medieval Europe and the revolutionary movements of the modern era, each phase in the development of theatre reveals shifting values and visions of society. As both mirror and maker of human experience, theatre continues to adapt—blending traditional techniques with contemporary innovations, expanding its reach beyond prosceniums into streets, communities, and digital platforms.

Origins in Ritual and Religion: The Birth of Theatre

Theatre as an art form did not begin as entertainment alone—it evolved from religious rituals, spiritual storytelling, and communal ceremonies that were central to early human cultures. Across civilisations, these performances were rooted in myth, worship, and social bonding, gradually developing into structured drama.

In ancient Greece, for instance, theatre emerged from the religious festivals honouring Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility. The chorus, which originally sang hymns (dithyrambs) in his praise, evolved into full-fledged tragedies by playwrights such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, featuring defined characters, dialogue, and dramatic tension.

In India, the foundations of dramatic tradition were laid out in the Nātyaśāstra, a Sanskrit treatise on dramaturgy composed by Bharata around 200 BCE. This text, deeply intertwined with Hindu philosophy, described theatre as a sacred act of rasa (aesthetic experience) and bhava (emotion), integrating music, dance, and acting to convey moral and spiritual truths. Classical Indian performances were often temple-based and celebratory of mythological tales.

In China, traditional forms like Chinese opera evolved from early ritual dances, combining symbolic movement, stylised music, and dramatic stories that often depicted historical heroes or moral conflicts. These performances were both ceremonial and educational in nature.

Similarly, in Japan, Noh theatre originated in the 14th century from Shinto and Buddhist religious rites, merging meditation, chant, and stylised performance. The masked Noh actor became a vessel through which spirits, gods, and historical figures could be invoked on stage.

Thus, across these traditions, early theatre was not merely a cultural product but a spiritual expression, where performance was meant to connect humans with the divine, reinforce communal values, and re-enact sacred stories. Over time, these ritualistic performances laid the groundwork for the evolution of secular and classical dramatic forms we study and perform today.

Classical Periods: Foundations of Dramatic Tradition

The Classical Period of theatre, spanning roughly from 500 BCE to 500 CE, marks a time when performance evolved into a formal, public, and literary art form. In this era, drama evolved beyond religious ritual into a structured cultural expression, with codified rules, themes, and performance spaces.

In ancient Greece, theatre was an integral part of civic life, especially during the Dionysia festivals in Athens. Playwrights like Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus transformed earlier choral hymns into complex dramatic forms. Sophocles introduced the third actor, enhancing character interaction and psychological depth, as seen in plays like Oedipus Rex. Euripides pushed boundaries with emotionally intense characters and modern social themes, evident in Medea. Greek tragedy explored human suffering, fate, and divine justice, while Aristophanes used comedy for satire and political critique.

In India, the Nātyaśāstra—a comprehensive treatise attributed to Bharata—laid the foundation for Sanskrit theatre. Composed around 200 BCE, it detailed everything from stage design to gestures, costume, music, and emotional theory. The central concept of rasa (aesthetic flavour or mood) governed the emotional experience of the audience. Classical Sanskrit plays by playwrights like Kalidasa (Shakuntala) blended romance, philosophy, and spirituality, performed in temple courtyards and royal courts with stylised gestures and musical accompaniment.

Meanwhile, the Roman theatre, heavily influenced by the Greeks, developed a more secular and entertainment-driven form. Plautus and Terence were renowned for their farces, characterised by stock characters, witty dialogue, and comedic misunderstandings. Roman theatres were large, open-air arenas that often featured integrated spectacles, including gladiator fights, acrobatics, and pantomimes. The emphasis shifted from divine reflection to mass appeal, setting the stage for theatrical architecture and audience engagement techniques that would influence European theatre for centuries to come.

The Classical Periods across these civilisations reflect a transition from the sacred to the secular, from chorus to character, and ritual to literature, defining the structural and thematic DNA of world drama.

Medieval to Renaissance Europe: From Sacred Allegory to Human Complexity

During the Medieval period (roughly 5th to 15th century), theatre in Europe was primarily religious and didactic, aiming to teach moral lessons and reinforce Christian beliefs. After the fall of the Roman Empire, theatrical traditions faded but were gradually revived through liturgical dramas performed in churches. These evolved into morality plays, mystery plays, and miracle plays—all of which dramatised biblical stories, saintly lives, and allegorical journeys of the soul. A well-known example is Everyman, an allegorical morality play where characters such as Good Deeds, Knowledge, and Death guide the protagonist through life and toward salvation. These performances, initially in Latin, eventually transitioned to public squares and wagons, utilising vernacular languages and drawing large audiences.

The Renaissance (14th to 17th century), which began in Italy and spread across Europe, marked a turning point. Inspired by classical antiquity, there was a revival of Greek and Roman ideals, focusing on individuality, realism, and human experience. This was the era of humanism, during which drama shifted away from purely religious themes and embraced secular narratives, complex characters, and poetic dialogue.

In England, this led to the flowering of Elizabethan drama, with William Shakespeare emerging as the most influential playwright. His works, such as Hamlet, Macbeth, and Twelfth Night, combined philosophical introspection with vibrant storytelling and rich character psychology. His Globe Theatre symbolised the merging of popular entertainment and literary artistry.

In France, Molière brought sophisticated comedy to the stage with plays like Tartuffe and The Misanthrope, blending wit, satire, and sharp critique of social hypocrisy. Italian commedia dell’arte, with its masked stock characters and improvisational style, also shaped popular performance across Europe.

The Renaissance ushered in permanent theatres, scripted plays, and professional actors. Theatre became a mirror to society, reflecting its politics, desires, and contradictions, setting the stage for the modern drama of later centuries.

Modern and Postmodern Theatre: Innovation, Politics, and Identity

The evolution of theatre in the 19th and 20th centuries was marked by experimentation, ideological engagement, and a deep questioning of traditional dramatic form. The Modernist movement, emerging during the 1800s, broke away from romantic idealism and classical conventions, giving rise to realism. This style sought to depict everyday life with psychological depth, social critique, and natural dialogue.

Henrik Ibsen, often called the “father of modern drama”, pioneered this with plays like A Doll’s House, which explored gender roles and individual agency in bourgeois society. Anton Chekhov followed with works such as The Cherry Orchard and Uncle Vanya, combining subtle emotional tension, social commentary, and the complexities of human relationships. These realist dramas created space for interior conflict and nuanced characterisation, moving away from moral allegory or heroic spectacle.

Parallel to realism, expressionism and symbolism emerged as reactions against naturalistic representation. Expressionist theatre, particularly in Germany, emphasised the inner emotional world through distorted sets, exaggerated gestures, and fragmented dialogue, reflecting the anxieties of industrialised, war-torn societies.

The early 20th century also saw the rise of political theatre, led by Bertolt Brecht, who developed the theory of the epic theatre. Brecht’s plays—such as Mother Courage and Her Children—utilised alienation techniques (Verfremdungseffekt) to prevent emotional identification and instead provoke critical thought. His work redefined theatre as a tool for social change, urging audiences to reflect on issues such as war, capitalism, and injustice.

At the same time, absurdist theatre, influenced by existential philosophy, questioned the very concept of meaning. Writers such as Samuel Beckett (Waiting for Godot) and Eugène Ionesco (The Chairs) created surreal, cyclical, and often nonsensical scenarios to reflect the disorientation and absurdity of human existence in a post-war world.

In India, the post-independence period witnessed a renaissance in Indian drama, marked by the rise of modern playwrights who drew from indigenous traditions while engaging with contemporary themes. Girish Karnad blended mythology, history, and folklore with existential and feminist concerns in plays like Hayavadana and Tughlaq, crafting complex allegorical narratives that are both thought-provoking and engaging. Vijay Tendulkar, on the other hand, used stark realism to expose violence, patriarchy, and political hypocrisy in plays such as Ghashiram Kotwal and Silence! The Court is in Session.

The postmodern turn, which began in the late 20th century, further deconstructed narrative logic, linear storytelling, and character unity. Influenced by performance art, multimedia, and globalisation, postmodern theatre became a collage of voices, genres, and aesthetics—often self-reflexive and open-ended. It challenged the very idea of theatre as fixed or authoritative, embracing fragmentation, irony, and audience interaction.

Modern and postmodern theatre reflect an era of profound artistic innovation, driven by social unrest, political change, and the search for identity. These movements continue to influence contemporary theatre, encouraging diversity, experimentation, and critical engagement with the world.

Contemporary Theatre: Innovation, Inclusion, and Impact

Contemporary theatre, spanning the late 20th century to the present day, is marked by its fluidity, hybridity, and responsiveness to global change. It no longer adheres to rigid structures or fixed traditions; instead, it embraces a plurality of voices, forms, and media, making theatre more inclusive, collaborative, and socially engaged than ever before.

One of the defining features of contemporary theatre is its integration of physicality and multimedia. Physical theatre companies like DV8 and Complicité fuse movement, dance, and visual storytelling with sparse dialogue, exploring complex themes through the body’s expressive capabilities. Simultaneously, the use of digital technology, video projection, live soundscapes, and interactive installations has expanded the boundaries of performance, creating immersive experiences that challenge the traditional divide between performers and audiences.

Contemporary theatre is also profoundly influenced by interdisciplinary practices, which merge performance with the visual arts, spoken word, activism, and digital media. It often draws from real-life testimonies, historical events, and current socio-political issues, resulting in devised and documentary theatre that reflects lived realities rather than fictional narratives.

Crucially, community-based theatre and street theatre have become vital tools for social change, education, and activism. Inspired by practitioners like Augusto Boal (with his Theatre of the Oppressed), such forms aim to empower marginalised voices, foster dialogue, and raise awareness about issues such as caste, gender, the environment, and displacement. In India, groups like Jana Natya Manch have brought political theatre to both rural and urban communities, utilising public spaces as stages and engaging spectators as participants.

Contemporary theatre actively challenges traditional notions of authorship, casting, and narrative authority. It welcomes non-professional performers, queer and disabled artists, and stories from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Issues of identity, migration, climate change, mental health, and digital alienation are explored with empathy and experimentation, often in non-linear, postdramatic, or site-specific formats.

In essence, contemporary theatre is not a single movement, but a living conversation—a dynamic blend of tradition and innovation, artistry and advocacy. It continues to reinvent itself in response to the times, proving that the stage remains one of the most potent spaces for reflection, resistance, and re-imagining the world.

Essential Theatre Terms

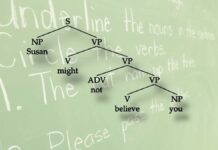

Blocking

The planned movement and positioning of actors on stage. Helps avoid chaos on stage and ensures clarity for the audience.

E.g., “Your blocking tells you when to walk downstage left or stand next to the chair during a scene.”

Monologue

A long speech delivered by one character, either to others or to themselves. It shows a character’s thoughts, emotions, and backstory in depth.

E.g., Hamlet’s “To be or not to be“ speech is a famous monologue.

Cue

A signal for an actor to speak, enter, exit, or perform an action. Cues can be words, sounds, or movements. Cues help maintain timing and coordination during performances.

E.g., The phone ringing is your cue to enter the stage.

Projection

Speaking loudly and clearly enough to be heard by the entire audience, without shouting. Ensures that every word and emotion reaches the audience.

E.g., Even in a large hall, your voice should be audible to the back row with good projection.

Improvisation

Acting without a script—spontaneously creating dialogue and action. Boosts creativity, quick thinking, and confidence on stage.

E.g., In a scene where someone forgets their line, another actor improvises to keep it going.

Upstage / Downstage

Upstage = back of the stage; Downstage = front of the stage near the audience.

These terms help in giving directions during blocking.

Stage Left / Stage Right

From the actor’s point of view, when facing the audience. (Opposite for the audience!)

Props

Objects used on stage by actors (e.g., books, cups, phones).

Backdrop

The painted background on stage, used to set the scene or mood.