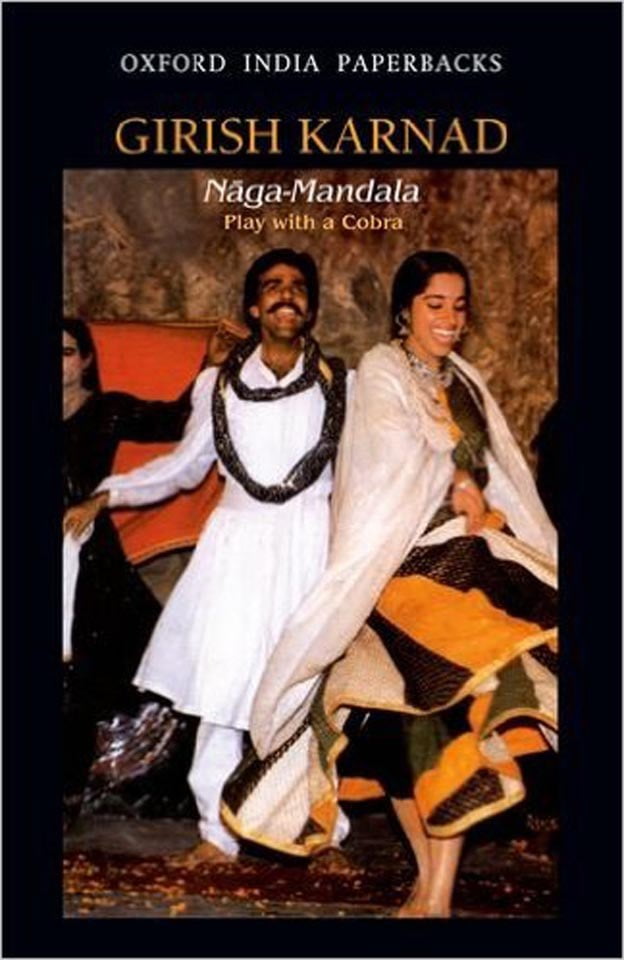

The play Naga-Mandala is based on the two oral stories from Karnataka that the playwright Girish Karnad heard from his mentor, Professor A K Ramanujan. Karnad through the play exposes the exploitation and incarceration of women that occurs through the institution of marriage and how myths display the fears of men in society and are thus inherently patriarchal and are used to control and restrict the actions of women. The play also mocks the idea of chastity and aims at the emancipation and empowerment of women.

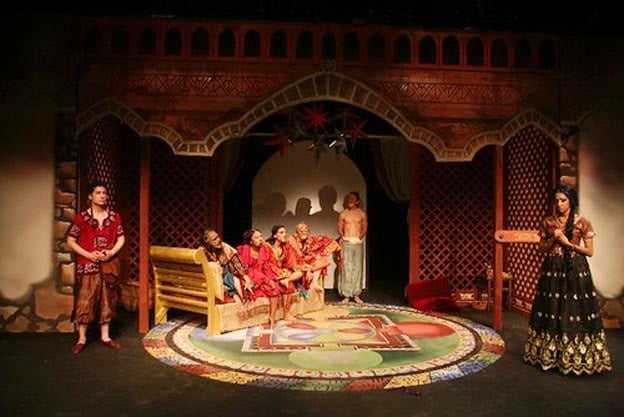

The play is also referred to as ‘Story Theatre’. Girish Karnad, a skilled storyteller, employs the technique of story within a story. The plot of Naga-Mandala has four narrative levels. At the first level, the author who commits the crime of writing boring plays that put the audience to sleep is sentenced to stay awake all night. The Flames (personified) of the village gather at the ruined temple where the author is wailing on the second level and continue to gossip. At the third level, the Flame who is the latecomer knows the story but refuses to share it with others, and the story escapes from her mouth while she is sleeping, and becomes the Story narrator. The Story tells the story of Rani, who is the central character in the plot. The structure of the temple and the relationships between the characters, which form upward and inward triangles, serve as the foundation for the entire Naga-Mandala. The temple represents Mandala and the snake represents vital energy. Rani’s relationship with the Naga alludes to Rani’s liberation and fulfilment from the clutches of patriarchy from a feminine standpoint.

The play is based in a rural setting and centred around the life of Rani, who is the everyday submissive rural Indian woman who is married off to a man by her parents, who arrange the marriage without taking into consideration her wishes. Her husband, a rich man named Appanna, which translates to any man. The name is a symbol employed by Karnad to highlight that this is the reality of most weddings that occur. It is to show how marriage is a patriarchal institution that has always been unfair to women.

Rani goes to Appanna’s house with the hopes of living a quiet, domestic life that she has been conditioned to expect but the reality she faces is horrendous. On the first day of their marriage, Appanna locks her in the house and goes to visit his mistress. This goes on every day as Appanna’s treatment of Rani is sub-human and he neglects her needs. She is kept isolated from society and due to the conditioning, she has undergone in her patriarchal set-up, she does not dare to question Appanna and better her condition. This stands to show that women in society lose the agency to question but when they violate the prescribed patriarchal norms, they are questioned immediately. The same is not the case for men who are free to do as they please.

Karnad shows how marriage is a patriarchal institution that has always been unfair to women. His play is full of symbolism that represents the unequal nature of our society and how women feel. As Rani’s emotional and sexual needs are not being met, she suppresses her urges and this suppression is meant to display how women are not able to claim their needs. She dreams of an eagle coming, taking her far away from Appanna’s world, which is another symbol of the repression of her desires. Her repressed desire to be loved and to be free gets expression in her fantasy where an eagle wants to take her away. Being a victim of extreme isolation and subjugation, her dreams function to fulfil her emotional needs.

As the story progresses, Rani comes across Kurudava who offers her a mystical root which if she feeds Appanna, will lead to him forgetting about his mistress and being completely devoted to her. Upon cooking the root, the potion takes a horrible red colour and she disposes of it in a nearby ant hill where a Naga(snake) drinks it. The snake falls in love with Rani due to the potion and takes the form of Appanna at night, praises her long hair and talks a lot about her parents and listens to her attentively. He also fulfils Rani’s sexual needs and soon she falls in love with the ‘Appanna’.

Rani however gets confused with the discrepancy in behaviour between the Appanna she sees at noon, who disregards her and leaves for his mistress and the Appanna at night, who treats her with care and is a sensual lover. However, she can’t question her husband. She must obey whatever she was told by her husband or any other male. Here nobody permits Rani to question anybody – Naga because of his deep passionate love for her and Appanna for his egoistic, male chauvinistic dominance. The women are seen as an object and not as human beings with an agency of their own.

Soon, Rani becomes pregnant which angers Appanna who calls her a harlot when she says that the child is his and she has done nothing wrong. She is taken to the village panchayat, where she must undergo a chastity test to prove her innocence. Nobody brings forth the question of Appanna being questioned for his misdeeds which again shows the two-faced notion of patriarchal justice that the panchayat was going to employ. Her test consists of her having to put her hand in a snake pit – if deemed pure, the snake would not bite her and if guilty of adultery, she would be poisoned by the very snake.

The Naga goes into the pit and makes an umbrella with his hood over her head and moves over her shoulder to make a garland. In an ironic situation, her infidelity comes to her aid in proving that she is a faithful wife. The panchayat declares that Rani is not only equal to a righteous man but is beyond human beings and is, in fact, a Goddess. Appana had to accept her with the child. But Appana was still in confusion because he knew that he was not the father of that child but he had no choice except to accept her. Thus, the anxious, scared woman finds within herself, courage and confidence and gains social respectability as she emerges victorious from the public trial, by the same public trial that was meant to condemn her. She now has more control of her life and, more importantly, respect.

There are multiple ends given by Karnad that talk of the fate of the snake. The most accepted is the case where the snake strangles himself to death upon seeing Rani reconcile with Appanna. Some days later, one day Naga thought to see Rani, so he went to the home where he found her with Appana. The Naga was very furious to see that so it decided to kill Rani but out of love, it stopped and turned into a small cobra and hid in her long hair. In the morning when Rani combs her hair the dead Naga falls and the play ends. But the listener was not satisfied with the sad ending so he provides a happy ending himself and that is when Rani combs her hair the alive Naga falls, Appana tries to kill it but Rani hides it back in her hair. The story comes to a close with Rani’s final remarks -“This hair is a symbol of my wedded bliss. Live happily in there forever”.

Through the play, we can see that women can only be on par with men by attaining a god-like status, but this is only the case if the status quo of society is maintained. In Rani’s case, society is still patriarchal and exploitative. However, she gains respect due to events that unfold during the trial. Her material reality has not changed. Hence, Karnad implies that as long as the existing material reality of women is not changed, where they are forced to be reliant on the closest patriarch in their life, only then can they attain freedom and respect by becoming god-like.

In Naga-Mandala, Girish Karnad incorporates Indian custom, myth, and folklore. In the context of cultural dilemmas and patriarchal ideology, the setting, themes, and plot all serve his intention of depicting the plight of an Indian woman and her ultimate struggle for freedom. In terms of people’s beliefs, the play reveals an abundance of Indianness.