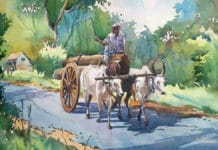

The poem Govinda’s Disciple by Rabindranath Tagore beautifully highlights the traits of a true master and his disciple who has not been able to overcome his materialistic nature. The setting of the poem comprises the lap of nature – an earthy haven covered with hills and streams, graced by the river Jamuna. This natural surrounding, untouched by civilization and modernisation, forms the perfect setting for this poem that deals with the renunciation of the material in favour of the divine and the spiritual.

The poem begins with natural imagery, transporting the readers from their worldly surroundings into the lap of nature. The river Jamuna can be seen at a distance, flowing swiftly and clearly through the wilderness. The bank of the river is lined with jutted rocks that make it seem as if the river bank is set into a perpetual frown. The landscape is surrounded by hills on all sides. The dense foliage of trees growing on the hills gave the hills a dark appearance. They were scarred by the many fast-moving streams that journeyed through the hills.

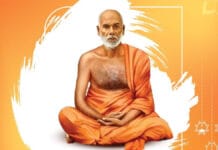

It was amid this wild habitat and natural beauty that the great guru Govinda, one of the founders of the Sikh religion, sat on a rock and read his scriptures. His study was interrupted by a visit from one of his disciples, Raghunath – a rich fellow who came bearing a gift for his guru. Bowing in front of Govinda, Raghunath said to his guru that he had brought a small present for him, in hopes that it would be worthy of the great sage’s acceptance.

Raghunath brings forth a pair of gold bangles studded with precious stones – an expensive gift indeed. Govinda picked one of the bangles up and twirled it around in his finger, while the diamonds on the piece of jewellery scintillated by refracting the sunlight.

Govinda was only observing one of the bangles when it suddenly slipped from his fingers and rolled down the stony bank and into the river. Taken aback by the loss of his precious gift, Raghunath screamed in disappointment and jumped into the water to retrieve the bangle he had brought for his guru. Govinda continued to sit on the rock and read his scriptures, unbothered by the frantic attempts of Raghunath to bring back his precious gift to him. The water too seemed unbothered by Raghunath’s search and continued to hide away the bangle as if it had decided to steal the same away from Raghunath.

Dripping with water, and exhausted Raghunath came back to Govinda, having spent the whole day looking for the bangle in the water. Through breathless pants, he told his guru that he could still fetch the bangle for him if only Govinda would show him where it fell. Govinda answered this request of his disciple in the most unexpected way. Picking up the second bangle, he threw it into the water as well, and said, “It is there,” implying that just like the first bangle, even the second one was now lost.

Govinda’s Disciple is a moral fable that deals with the relation between Govinda and his disciple Raghunath. It is a subtle critique of materialism that goes by in the name of spiritual respect. Govinda’s Disciple brings into focus the master-disciple relationship and shows us how the master teaches values through living examples of painful experiences.

The central idea of Govinda’s Disciple revolves around the renunciation of one’s attachment to material possessions to create space for divinity to enter our minds and make it fertile for spiritual endeavours. Human’s pursuit of wealth and the value we attach to materialistic things act as the biggest impediment on our paths for spiritual attainment. Disciples like Raghunath, whose minds are still occupied with wealth and luxuries, can never achieve clarity on their real divine purpose in life, for they are too busy amassing and showing off wealth.

In this poem, the great Sikh guru Govinda by throwing his gift of bangles into the river offers a profound lesson to his disciple and makes him realize that he was only satisfying his ego and not showing real selfless regard for his guru. What is left unsaid is more eloquent and effective. The abrupt end thus gives the reader a powerful message.