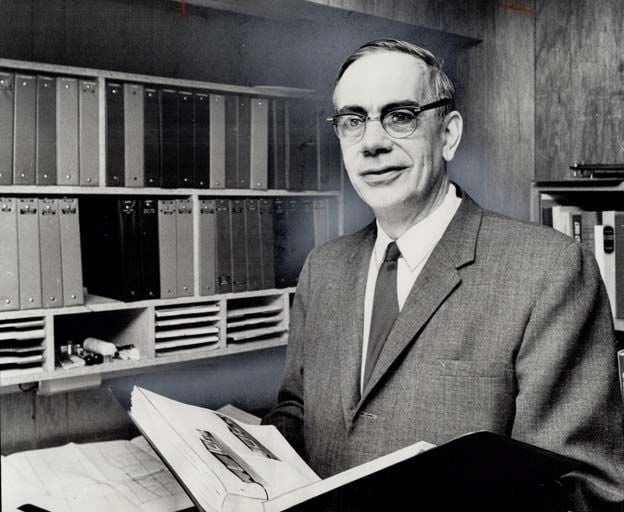

The Gleason Method in linguistics, developed by influential American linguist Henry Allan Gleason, is a systematic approach to analysing and understanding languages. This method includes a variety of linguistic analysis techniques, primarily focusing on descriptive linguistics, which is the study of language in its current form without judging it against prescriptive norms.

Gleason was mainly known for his work in developing techniques for field linguistics, including methods for language documentation and analysis when working with languages that have not been formally recorded or studied.

In An Introduction to Descriptive Linguistics, a textbook by Gleason, he provided comprehensive methodologies for linguistic fieldwork and analysis, likely reflecting the essence of what might be termed the Gleason Method. These would include best practices in collecting language data through direct interaction with native speakers, transcribing and analysing linguistic features, and understanding language in its cultural context.

Features of Descriptive Linguistic Analysis

Phonetics and Phonology

The analysis of the sound systems of languages, including the study of individual sounds (phonetics) and the patterns and systems of these sounds (phonology).

Morphology

The study of word formation and structure, including the analysis of morphemes, the smallest grammatical units in a language.

Syntax

Investigating the structure of sentences and the rules that govern the combination of words into phrases and sentences.

Semantics

The study of meaning in language includes word meanings, sentence meanings, and the principles governing the interpretation of meaning in context.

Language Typology

Comparing languages to categorise the different types and understand the range of potential structures in human language.

The Gleason Method

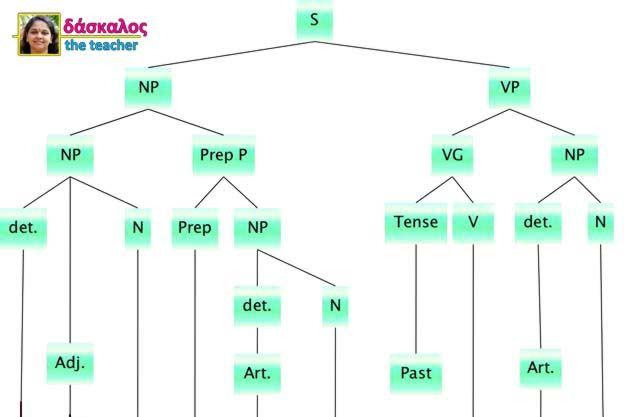

The grammatical constituents in a sentence, like Noun Phrases, Verb Phrases, Adverbials and Preposition Phrases, can be further divided into categories such as Nouns, Adjectives, Verbs, Tenses and Morphemes.

Now, the question arises as to how we should make the cuts. The answer lies in the notion of ‘expansion’.

A sequence of morphemes that patterns like another sequence are said to be an expansion of it. In such cases, one sequence can be replaced by another as similar sequence patterns appear in the same environment. Here is an example of similar sequences in the expansion that can fit into the same slot:

(1) Daffodils

(2) Yellow daffodils

(3) The yellow daffodils.

(4) The yellow daffodils with a lovely look.

The elements 2, 3 and 4 are expansions in the above set, i.e., ‘daffodils’ is the headword, whereas the other words in 2, 3 and 4 are modifiers. Incidentally, the examples above can be grouped under noun phrase (NP).

There are no hard and fast rules for determining the ICs of a construction. The native speaker’s intuition tells him where the most fundamental cut should be. He will cut it into pairs where he feels the closest and the most direct relationship exists. Gleason suggests the following methods to determine the ICs of a construction.

(1) The primary method is that of comparing samples. For example, let us divide the construction of her son’s school into its ICs. This may be divided into four ways:

(a) her/son’s school

(b) her son’s/school

(c) (her) son’s (school) –son’s is one IC and her…school another

(d) her/son’s/school

If the construction had only two constituents, there would be no problem. E.g., old/man. Let us find a two-word construction which is directly comparable with her son’s school, some construction that can occur in similar environments and is alike in the features used to mark syntactic relationships. Sam’s school is such a construction. Since Sam’s can replace her son’s, the two may be regarded as equivalent, and we will divide the construction as her son’s/school; and Sam’s/school. Such a comparison helps us identify ICs in many cases but not all. Great care has to be taken to make sure that the constructions compared are comparable.

(2) Suprasegmentals play a decisive role in assisting the native speaker to determine the IC cuts. These features are the strong evidence for syntactic structure. Only constructions with similar stress and intonation should be compared since, occasionally, pairs of utterances of identical constructional types may be pronounced with different stress and intonation.

(3) One helpful test for determining ICs is freedom of occurrence. If we break up an utterance into smaller parts, we find that these parts occur in other utterances, too. The shorter portions, like words and inflectional endings, occur more freely than the longer ones. A constituent sequence has greater freedom of occurrence than one that does not. Thus, if we cut Old/Light Church as we would old/lighthouse, we will find that Light Church occurs in very few contexts, such as New Light Church, whereas lighthouse occurs in a great variety, such as a new lighthouse, pretty lighthouse, etc. The native speaker learns the correct cut through familiarity with the constituents in several contexts.

(4) Yet another valuable test for ICs is substitutability. When we compare ‘her son’s school‘ with ‘Sam’s school‘, we assume they have the same constructional pattern and constituents. ‘Same’ here does not mean identical or even similar in form or meaning, but only that they are alike in their potentiality for entering into constructions; they should enter into several constructions otherwise identical, i.e., one should be substitutable for the other.

Key features of the Gleason Method

Structural Analysis

The Gleason Method involves analyzing the structure of language at various levels, including phonology (sounds), morphology (word structure), syntax (sentence structure), and semantics (meaning). Linguistic elements regarding their internal structure and relationships to other elements within the language system are examined.

Systemic Analysis

This approach also considers language a system of interrelated elements rather than isolated units. Linguistic elements are analyzed about one another and within the broader context of the language system. This systemic perspective allows a deeper understanding of how language functions as a communicative system.

Comparative Analysis

The Gleason Method often involves comparative analysis, where linguistic structures and systems are compared across different languages or language varieties. By comparing languages, linguists can identify universal patterns and principles of language structure and organization, as well as language-specific features and variations.

Functional Perspective

The Gleason Method emphasizes the functional aspects of language, focusing on how linguistic structures and systems serve communicative functions in social contexts. This functional perspective considers how language conveys meaning, expresses identity, and interacts with others within a given linguistic community.

Pedagogical Application

The Gleason Method has been applied in language teaching and learning contexts, particularly in the field of second language acquisition. By focusing on the structural and systemic aspects of language, this approach can help learners develop a deeper understanding of language structure and usage and improve their communicative competence.

In essence, the Gleason Method promotes a rigorous, scientific approach to studying the structure and use of language, with a strong focus on observation and evidence. It guides linguists in documenting and understanding the complexities of language without imposing any preconceived notions or external grammatical rules.