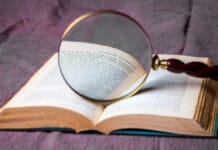

The Truth about Me: A Hijra Life Story provides a firsthand perspective on the challenges and discrimination faced by transgender individuals in Indian society. It’s more than just a personal narrative but an in-depth exploration of the complex social dynamics, prejudice, and stigmas that the Hijra community faces in India. It sheds light on the social isolation, economic restrictions, and systematic exploitation they often endure. The narrative charts Revathi’s life journey from being born and raised as a boy in a traditional South Indian family, her realisation of not fitting into the accepted gender roles, her consequent transformation into a woman, and finally, her acceptance as a Hijra. She poignantly chronicles the bullying and discrimination she faced in her childhood and youth, the sexual abuse she underwent, and her struggle to affirm her identity.

The book has 28 chapters. It follows the chronology of Revathi’s life. Born a male in a peasant family of modest means in a village in Namakkal Taluk in Salem, Tamil Nadu, Doraisamy – as he was named by his parents – discovered in early childhood that he was very different from the other boys of his village. At school, he shunned boys’ games, preferring to play with girls and dressing up like a woman in his mother’s clothes. As the years passed, instead of his ‘feminine’ ways falling aside, as his parents had hoped, Doraisamy increasingly began to feel that he was a girl, although trapped within a male body for no fault of his own. And the more ‘feminine’ he dressed and behaved, the more he was taunted by his peers at school and his parents and siblings at home. He had no one to share his pains with until he finally met a group of young gay men in a town near his village. For the first time, he discovered that he was not alone in this world, not the only boy who felt and behaved like a girl. From these men, he found that it was indeed possible for a boy to become a girl or, more precisely, a hijra – a eunuch.

In his late teens, Doraisamy fled his home, unable to bear the constant torments he suffered daily from his family and neighbours. He took a train to Delhi, where he found himself in a world utterly different from his little Tamil village. There, he met a group of hijras, who took him under their wing. He began living as a member of the hijra household, observing the various rituals and customs specific to the hijra community – which the book describes in intricate detail. Finally, the head or guru of the hijra household agreed to initiate him into the community – or, in other words, to make him her chela or disciple – by allowing him to have his male sexual organs removed. There are two ways to do this: either by a doctor who does a surgical excision in a hospital or by a hijra dai using a primitive and painful method. The latter is dangerous and sometimes fatal, but men who become hijras in this manner are accorded tremendous respect in the hijra community. Doraisamy chose the former. The operation was short and swift but still excruciatingly painful. Within two hours, Doraisamy was transformed into the woman he always wanted to be – or, more precisely, the woman he always felt and even knew he was. Christened Revathi by her guru, she became a full-fledged member of the hijra community, no longer just a kothi, an effeminate male.

Revathi had hoped that once she turned into a ‘woman’ or a hijra, she would finally be at peace with herself. But, she soon discovered life as a hijra was harsh, even cruel. She describes in painful detail the sordid life in her guru’s home, the constant quarrels with her guru bais, fellow hijra disciples of her guru, who are sexually and economically exploited by the latter, the threats and violence from men in the streets, the abuses she had to constantly suffer from strangers for being a hijra, a veritable outcast, the desperate poverty that most hijras have to face because no one is willing to employ them. She took to doing badai work, singing and dancing at people’s homes on the occasion of a birth or a marriage, a custom, now rapidly dying out, that accorded a measure of respect to hijras in traditional Indian society. But what she earned from this work was meagre, hardly sufficient to make ends meet. Thereupon, she joined a group of fellow hijras to go from shop to shop asking for money and food, but there she had to contend with relentless harassment and a relentless barrage of insults.

Meanwhile, she discovered her sexual desires – as a ‘woman’ – but soon realised that although she pined for a regular ‘life’ as a married ‘woman’, no man would ever take her as his wife. Finally, she was forced, like many other hijras, to do sex work to survive and in the hope of finally finding the love of a man. She shifted to Mumbai, where she took up with a hijra household, becoming the chela of a hijra guru who headed a team of sex workers, both women and hijras.

Life as a hijra sex worker, which Revathi describes in painful detail, is brutal. She speaks of her horrific degradation at the hands of fellow hijras, their gurus, drunken men, and the police. Hauled to a police station, she is brutally assaulted sexually. A rowdy rapes her and robs her meagre possessions. A bunch of thugs threatens to kill her. She seeks refuge in bars and becomes a compulsive drinker. Life as a hijra is one never-ending series of torments, and the man she had dreamt of would one day find her and take her as his spouse never enters her life. Finally, unable to bear her hellish existence any longer, she escapes and returns home to her village, expecting her family to comfort her. Once there, however, she realises that she is dead as far as they are concerned. The scorn she meets at their hands is hardly less tormenting than what she had to endure as a sex worker in Mumbai. She stays in her village for a few months but has now developed the inner confidence to fight back. When people insult her, she no longer remains silent as she used to. A hijra is also a human being worthy of respect; she answers back and tells her tormentors to lay her off.

A significant turning point in Revathi’s life occurs when, after shifting from her village to Bangalore, where she works for a time selling her body, she meets with activists of an NGO working for the justice of sexual minorities. The NGO offers her a job, which she takes up, though modestly paid, to escape the brutal life as a sex worker. She starts as a peon, doing odd jobs in the office. Still, her grit and intelligence win her greater organisational responsibilities, where she realises that an alternate life is possible for people like her. She attends activist meetings and reads literature about hijras like herself, where she learns that hijras, like other marginalised communities, can and must stand up for their rights. They deserve the same rights as everyone else; she now knows: to be recognised by the state as equal citizens, to have ration cards, to vote and stand for elections, to study and be decently employed, to marry and adopt children, and to be free of hate, scorn and prejudice. She begins mobilising her fellow hijras on these lines.

Revathi’s new-found joy of being liberated from begging and sex work forced on hijras by a society that denies them any other means of livelihood and of working for her community proves to be short-lived, however. Her guru and chela are murdered in separate incidents – both fall tragic victims to brutal thugs. To add to her misery, the man – who claims to be bisexual – who marries her, an activist in the NGO she works with, abandons her for months despite his previous professions of love for her and her profound dedication to him. She finds, to her horror, that she is now all alone in the world. Instead of caving in and giving up, however, she defies the heavy odds that she faces. She does this by deciding to write her autobiography, to tell the world what life for hijras is all about, and to insist that society and the state must give them their due.

The book’s tone is frank and straightforward, making the injustices faced by the Hijra community all the more stark and the resilience shown by Revathi even more remarkable. In its critically acclaimed examination of intersectionality – identity, gender, caste, and sexuality – Revathi’s autobiography invites readers to reevaluate the conventional, binary understanding of gender, urging them to appreciate and respect diversity through a poignant depiction of strength amidst adversity.

Through her journey of self-discovery and acceptance, Revathi provides an intimate and authentic account of the challenges faced by the transgender community in India. Her raw and honest storytelling allows readers to empathise with her struggles and understand the complexities of her identity. By sharing her triumphs and hardships, Revathi educates and inspires readers to question societal norms and advocate for equal rights for all individuals. Through her experiences, Revathi sheds light on the discrimination and violence that transgender individuals often face in Indian society. She fearlessly exposes the existing ignorance and prejudice, challenging readers to confront their biases and work towards a more inclusive society. With her powerful narrative, Revathi not only gives a voice to the transgender community but also encourages others to embrace diversity and celebrate the uniqueness of every individual. Her story catalyses change, urging readers to stand up against injustice and fight for a world where everyone can live authentically and with dignity.

One of the strengths of The Truth About Me: A Hijra Life Story is Revathi’s ability to capture the raw emotions and experiences of her journey as a transgender woman. Her honest and vulnerable storytelling allows readers to connect with her deeply, making her struggles and triumphs feel personal and relatable. Revathi’s advocacy for transgender rights shines through the pages, bringing attention to the societal issues that must be addressed for change and acceptance.

However, one concern for the book could be the limited scope of Revathi’s personal experiences. While her story is undoubtedly powerful and vital, some readers may yearn for a more diverse range of perspectives on transgender life in India. Additionally, the narrative may focus solely on Revathi’s journey, leaving readers wanting to hear from other voices within the transgender community. Revathi’s bravery and resilience in the face of discrimination and adversity are truly inspiring despite this limitation. Her story serves as a reminder of the strength that can be found within oneself when faced with societal challenges.

Revathi’s book provides a valuable and significant contribution to understanding Hijra’s life and experiences. Through her personal story, she sheds light on the struggles, discrimination, and challenges faced by the transgender community in India. The book offers an intimate portrayal of the emotional and physical journey of a Hijra individual, allowing readers to gain a deeper understanding of their lives and the complexities they navigate daily. It breaks down stereotypes and misconceptions surrounding the Hijra community, fostering empathy and compassion among readers. Revathi’s narrative promotes awareness and acceptance, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and understanding society.