Cognitivism is a theory of learning that focuses on processes of the mind. Cognitivist learning states that the way we learn is determined by the way our mind takes in, stores, processes, and then accesses information. When we learn new things, our brains are able to transfer the information we have learned and apply the information to new situations or problems. This is the main goal of most learning theories.

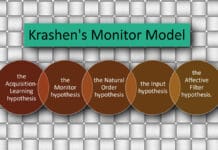

A cognitive theory of learning sees second language acquisition as a conscious and reasoned thinking process, involving the deliberate use of learning strategies. Learning strategies are special ways of processing information that enhance comprehension, learning or retention of information. This explanation of language learning contrasts strongly with the behaviourist account of language learning, which sees language learning as an unconscious, automatic process.

Cognitivism, also known as cognitive learning theory, helps in developing better programs for learners because it uses research that focuses on the brain and mental processes for acquiring and using new information. Developing a strong knowledge of cognitivism can help anyone who is attempting to teach new information or concepts to others.

Even when a student is trying to learn something new, there is usually some sort of prior knowledge that they can use to anchor that new information and connect the new knowledge to it. That is the basis of cognitivism. The mind is basically an internal processor that uses our internally stored information and connects it to external factors in order to create new learning. Because learning involves activating pre-existing knowledge and gathering information from previous experiences to make sense of our world, cognitivists believe that their theory is the primary foundation for explaining how we learn things. Cognitivism is viewed as the mainstream for all research and foundations of learning design.

The mind is like a computer. When it comes to learning, cognitivist theory focuses on the process of learning and acquiring new information. Cognitivism is the theory that focuses on how we receive, organize, store, and recall information in our minds. One of the main contributors to cognitivism was Jean Piaget. Piaget identified stages of cognition that all children pass through universally based on their age and stage of mental development. He argued that a child has to understand a concept before s/he can acquire the particular language form which expresses that concept. A good example of this is seriation. There will be a point in a child’s intellectual development when s/he can compare objects with respect to size. This means that if you gave the child a number of sticks, s/he could arrange them in order of size. Piaget suggested that a child who had not yet reached this stage would not be able to learn and use comparative adjectives like “bigger” or “smaller”.

The predictable stages of cognition that Piaget identified were sensorimotor, pre-operational, concrete operational, and formal operational. Piaget stated that “Teaching means creating situations where structures can be discovered.” Real learning depends on our ability to access information from our long-term memory when we need it.

Object permanence is another phenomenon often cited in relation to cognitive theory. During the first year of life, children seem unaware of the existence of objects they cannot see. An object which moves out of sight ceases to exist. By the time they reach the age of 18 months, children have realised that objects have an existence independent of their perception. The cognitive theory draws attention to the large increase in children’s vocabulary at around this age, suggesting a link between object permanence and the learning of labels for objects.

When we learn something new, the process that occurs in our minds begins with the activation of prior knowledge. The prior knowledge that is already in our minds can serve as a hook to grab onto the new information and form a connection to it. If we have a schema, or a familiar structure to compare it to, then the knowledge can flow through the pathways of our brains and connect. The schema is the framework that learners use to understand new information that they are receiving. In the case that a student is learning information that opposes something they already believed to be true, they must accommodate and work to unlearn that previous concept, and then replace it with the correct concept by making a new connection. At first, the information we are exposed to goes into our short-term memory. If the learning is made meaningful to us or if we are able to successfully connect it to something we know, it is more likely that we will be able to store the new information in our long-term memory. Our brains already have knowledge pathways, and when we acquire and build new knowledge, the pathways become stronger.

Cognitive Learning Strategies

Educators and learners alike can use different strategies to offer a richer learning experience, where hopefully the new knowledge that is acquired can be stored away into long-term memory and become part of our permanent knowledge base. It is important to be clear about the task involved and what type of learning is required to employ the task for that strategy to be effective. There are strategies that can be used at the beginning, middle, and end of the learning cycle in order to conceptualize the learning and build new knowledge.

Beginning strategies: Anticipation guides and KWL charts. An anticipation guide is similar to a pre-test. It allows the learner to look at questions before the concept is taught, try to guess correct answers, and also discuss or wonder what the lesson will be about based on the anticipatory set of questions. A KWL (Know, Want to know, Learn) chart is a table that allows students to write down what they know about a topic and what they want to know about it. During or after the lesson cycle they fill in the “L” section of the chart according to what they are learning.

Middle strategies: Concept maps, sorting activities, classifying information, and note-taking. Concept maps, also known as mind maps, are visual representations of information. Another term for concept maps is graphic organizers or thinking maps. They can take the shape of tables, T-charts, Venn diagrams, bubble maps, timelines, and tree maps (to branch off concepts into details). Sorting activities, or concept sorts, are more hands-on and are usually prepared by the teacher ahead of time so that students can categorize concepts using cards or strips of paper. Classification of information, either by sorting or concept mapping, is effective because it supports the development of schema in the brain so that further connections can be made. Different methods of note-taking styles can be employed to organize information, such as outlines or Cornell-style notes.

Ending strategies: Reflection questions, compare and contrast, completing the “L” section of the KWL chart, drawing a picture, or talking to a partner about what they learned. Learners can also choose a product to display what they learned, such as a poster or a pamphlet. There are limitless opportunities to formatively assess whether a new concept or skill has been learned. Creating a product is a way for the learner to cement their learning in a way that makes sense to them.

Limitations of the Cognitive Theory

During the first year to 18 months, connections of the type explained above are possible to trace but, as a child continues to develop, so it becomes harder to find clear links between language and intellect. Some studies have focused on children who have learned to speak fluently despite abnormal mental development. Syntax in particular does not appear to rely on general intellectual growth.