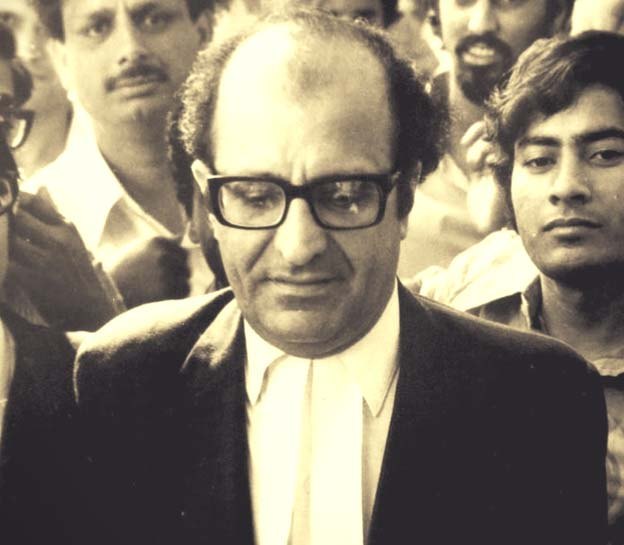

Nanabhoy “Nani” Ardeshir Palkhivala was an eminent Indian jurist, constitutional expert and liberal economist. Born in Mumbai in 1920, he had his master’s degree in English Language and Literature. Later, he enrolled at the Government Law College, Mumbai, where he discovered that he had a gift of unravelling the intricacies of jurisprudence. He started practising in the Supreme Court of India and became one of the great interpreters of the Constitution of India. He was committed to the legality and morality of the Constitution. Nani A Palkhivala had appeared before the Supreme Court several times when constitutional issues were involved. He was offered a seat in the Supreme Court in 1963, which he declined. Later, he was offered the position of Attorney-General in 1968 by Govinda Menon, then Law Minister in the Government of India, which he also refused. In 1977, he was appointed as Indian Ambassador to the United States by the government headed by Morarji Desai, and he served in that capacity till 1979. There are several instances where Palkhivala appeared in the rescue of the spirit of the Constitution. Kesavananda Bharati vs. State of Kerala case is an example of such an instance that made him prominent.

The chapter titled Centre-State Relations: Union Government, Not Central Government is originally a speech delivered by Palkhivala in Mumbai on the 18th of February, 1972, as a part of Heras Memorial Lecture, which delves into the intricacies of India’s federal structure. Palkhivala’s discourse critically examines the relationship between the Union and the States, emphasising the importance of cooperative federalism and the distinction between the terms Union Government and Central Government. It discusses the constitutional rights guaranteed to the states and how the Central Governments took them away. His speech revolves around the idea that India is a federal state. Indian Constitution borrowed the concept of federalism from the Canadian Constitution. India is a federal system but has a more tilt towards a unitary system of government. It is sometimes considered a quasi-federal system as it has features of both a federal and a unitary system. A part of Article 1 of the Indian Constitution reads, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of states”. Elements of federalism were introduced into modern India by the Government of India Act of 1919, which separated powers between the Centre and the Provincial Legislatures.

India is a federal country because of the following reasons:

- There are levels of government -Central Government, State Government and Local Government.

- Each level of government administers over the same region, but they have their own jurisdiction in administration, taxation and legislation.

- The Government at each level derives its power from the Constitution of the country. Thus, the Central Government cannot quickly dilute the powers of the State or Local Governments.

- The basic principles of the Constitution and the rights given to the people cannot be changed by only one tier of the Government. It requires the consent of governments at both levels.

- Both levels of the Government can collect taxes from the people according to the guidelines of the Constitution of the country.

- The Indian Constitution contains three lists of subjects on which the Union and the State Governments may form laws. Only the Central Government can make laws in the union list and the State Government in the state list. Subjects related to the interests of both Central and State Governments are included in the concurrent list.

Palkhivala points out that the Union Government is acting as the centre. He adds that it should not be a Central Government but a Union Government. He delivered this speech immediately after India won the Bangladesh Liberation War and the Indo-Pakistani War in 1971, which made the Central Government stand in the limelight. These achievements made the government slightly despotic and dominant in trying to control the privileges of other constitutional functionaries like the states, the judiciary and the people. We had seen this increasing despotism culminating in the emergency period in 1975 against the democratic principles and fundamental values of the Constitution.

Nani Palkhivala delivered this speech 22 years after India became a republic. He says various principles underlying the Constitution were drawn overboard during this period. The values of human dignity and public justice have been subverted. The provisions regarding the powers of the states, including the powers to deal with industry, trade and commerce, had been perverted. The Central Government has disrespected many of the provisions that guaranteed certain powers to the states. He adds that the states were reduced to positions with far less power to deal with industry, trade and commerce than the second-class native states during the British Raj. He argues that the Princely States during the British Raj were treated better. Significantly, the Constitution speaks about the Union, not the Centre. The Union Government claims that it is a Central Government. They are assuming powers beyond what is given in the Constitution. The concept of a Centre is adversarial with the constitutional scheme of the Union of States.

Palkhivala even goes so far as to argue that in the exercise of significant powers, the states have the right to go wrong in freedom rather than go right in being enthralled by the centre. He claims that there is nothing wrong in states going wrong to uphold their freedom. The states need not live in slavery under the centre. The Constitution guaranteed good checks and balances between the powers of the states and the Central Governments. The Constitution has legal and moral provisions to ensure that the rights of the states are protected, and India remained the Union of States, not an administrative unit with a strong centre. This concept of a strong centre is only a self-cited concept by the Union Government.

In the concluding part of the speech, Palkhivala assures that the time will come soon when the states refute the centre’s claims and try to win their constitutionally guaranteed powers. The day of inevitable fall of unconstitutional and unjust supremacy exercised by the Union Government over their State Governments will soon happen. To cement his reassurance, he borrows the words of famous American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, who claims that “the man who thinks he may live as freely as his unconsidered desires prompt him and yet not carry the burden of an eventual reckoning, is binding his own life to a hollow dream. Whoever sins against his fellows or himself pronounces his own sentence thereby”. He argues that though its operations are often unseen and not always be found in the stone-built courts, justice will perform its operations whenever and wherever necessary. If the Union Government disrespects the rights of the states, they will, sooner or later, raise in rebellion to refute the claims of the Central Government.

Even after Palkhivala’s speech, we have seen many instances of clashes between the centre and the states in India, especially when different political parties rule the centre and the states. So, Palkhivala’s speech has contemporary relevance and will also be pertinent in the future.

Thesis and Purpose

Palkhivala’s primary thesis is that the term Union Government reflects the spirit of India’s Constitution more accurately than Central Government. He argues that the framers of the Constitution envisioned a federal structure where the Union and the States share powers and responsibilities rather than a central authority exerting dominance over subordinate states. This distinction is not merely semantic but is foundational to understanding and preserving the balance of power in the Indian Federation.

Historical Context and Constitutional Framework

Palkhivala begins by providing a historical context for the creation of the Indian Constitution. He references the debates in the Constituent Assembly, where there was a clear intention to adopt a federal system, albeit with a strong centre to maintain unity and integrity. He points out that the term “Union” was deliberately chosen to signify that the Indian federation is indestructible and that no state has the right to secede.

The Constitution delineates the powers of the Union and the States through three lists: the union list, the state list, and the concurrent list. Palkhivala underscores that while the Union has overriding powers in certain areas, the federal structure is meant to be cooperative and respectful of state autonomy.

Critique of Centralisation

Palkhivala critiques the trend towards centralisation of power, which he views as contrary to the federal principles enshrined in the Constitution. He argues that excessive centralisation can lead to inefficiencies, resentment, and a weakening federal spirit. The encroachment of the Union on state subjects, the misuse of Article 356 (President’s Rule), and the Central control over state finances through the Planning Commission (now replaced by NITI Aayog) are examples he cites to illustrate the erosion of state autonomy.

Emphasis on Cooperative Federalism

Palkhivala advocates for cooperative federalism, where the Union and the States work together harmoniously towards common national goals. He emphasises that cooperation and coordination should guide Centre-State relations rather than confrontation and coercion. He highlights the importance of mechanisms like the Inter-State Council and the Finance Commission in fostering dialogue and cooperation between different levels of government.

Legal and Judicial Interpretations

Palkhivala also delves into legal and judicial interpretations that have shaped Centre-State relations. He discusses landmark Supreme Court judgments that have reinforced the federal character of the Constitution, such as the Kesavananda Bharati case, which established the basic structure doctrine. This doctrine asserts that certain fundamental features of the Constitution, including federalism, cannot be altered even by a constitutional amendment.

Recommendations for Strengthening Federalism

Palkhivala offers several recommendations for strengthening federalism in India. He calls for greater financial autonomy for states, reforms using Article 356, and more robust institutional mechanisms for intergovernmental dialogue. He also advocates for a clearer demarcation of responsibilities and resources to avoid overlapping jurisdictions and conflicts.

Nani A Palkhivala’s lecture, Centre-State Relations: Union Government, Not Central Government, is a seminal analysis of India’s federal structure. It underscores the importance of preserving the federal spirit envisioned by the Constitution’s framers and cautions against the dangers of centralisation. By emphasising cooperative federalism, Palkhivala’s insights remain highly relevant in ensuring a balanced and harmonious relationship between the Union and the States, which is crucial for the country’s unity, integrity, and democratic functioning. His critical appreciation of the federal system guides policymakers, legal experts, and scholars in navigating the complexities of Centre-State relations in India.