The Romantic and Victorian periods were two of the most transformative eras in English literature, with each bringing distinct styles, themes, and philosophies to poetry and criticism. While the Romantic period, roughly from 1798 to 1837, emphasised emotion, individualism, and nature, the Victorian period, which existed during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837 to 1901), dealt with social issues, realism, and the complexities of modern life. Both movements were, to some extent, reactions to cultural changes.

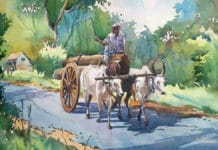

Romanticism was, in part, a reaction against the Industrial Revolution. As urbanisation and factory production swept across Europe in the 18th century, writers looked to nature as a way to reclaim a way of life that was being threatened. Similarly, increased economic inequality through the 19th century led Victorian writers to want to expose the horrors of poverty. Disenchanted by the decline of religious belief in Europe, poets and novelists saw their role as chronicling the bleakness of the modern world.

One of the chief markers of Romanticism is a deep belief in the power of nature. Poets such as Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth and Coleridge are famous for looking to the natural world for inspiration in a corrupted world. This idealism led them to write sonnets that contemplate the beauty of nature. By contrast, Victorian writers had little faith in nature to overcome the problems of the world. Poets and novelists such as Hardy, Tennyson and Browning depicted the world as dark and disturbed. Charles Dickens’ novels, meanwhile, showed the misery of the working poor.

Romanticism is also known for its emotional outbursts. Romantic poetry is notable for its sudden expressions of joy, sadness and excitement. Victorian literature, on the other hand, takes literature as a deliberate craft. Using careful structure, Browning’s My Last Duchess, for instance, is a poem that uses irony to play with the reader’s expectations. Similarly, Victorian novels are known for their long and complicated plots.

The differences between Romanticism and Victorianism are apparent in the contrasting ways they use language. Because Romantic literature is emotionally expressive, it often uses phrases such as “Oh!” to give the impression of a sudden surge of feeling. This over-the-top use of language gave way to a more restrained use in Victorianism. Because Victorian literature sought to document the world as it was, it tended to use modern expressions and language and made less use of flowery metaphors and images.

Emotion

Emotion was central to Romantic poetry. Poets like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge emphasised emotion as the foundation of poetry, valuing personal feelings, imagination, and the expression of intense emotional experiences. In his Preface to Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth described poetry as the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings”. Romantic poets often focused on the sublime and the beautiful to evoke emotions of awe, terror, love, and melancholy. While Victorian poetry also engaged with emotions, it often did so in a more controlled and reflective manner. Victorian poets like Alfred Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning explored emotional complexities, usually reflecting on social issues, human suffering, and existential dilemmas. The emotional intensity of Romantic poetry was tempered by a Victorian sense of moral responsibility and a concern for social justice.

Spontaneity

The Romantics celebrated spontaneity in thought and expression, seeing it as a key to genuine creativity. They believed that poetry should flow naturally, driven by a moment of inspiration. This spontaneity was seen as a way to access deeper truths and emotions, unlike the calculated, reasoned approaches of the previous Enlightenment period. Victorian poets valued spontaneity but were more inclined to deliberate over their language and form. While they appreciated the Romantic ideals, they sought to balance spontaneity with discipline and structure. Victorian poetry often involved a more crafted approach, reflecting a concern with social and philosophical issues that required careful thought and articulation.

The Individual

The Romantic poets elevated the individual to a central position in their works. They saw the poet as a unique visionary, capable of perceiving deeper truths and providing insights into the human experience. The focus was on personal experience, introspection, and the individual’s relationship with nature and society. Victorian poetry also highlighted the individual but often placed the individual within a broader social context. Poets like Matthew Arnold and Elizabeth Barrett Browning were concerned with how individuals interacted with society and their moral obligations. The Victorian period was marked by a tension between the individual’s desires and society’s demands.

Poetic Diction

The Romantics rejected the artificial and ornate language of 18th-century poetry. Wordsworth, in particular, argued for a “language used by men,” advocating for simplicity, clarity, and common language to make poetry accessible to everyone. While Victorian poets continued to use more natural language than their 18th-century predecessors, they often experimented with form and diction to suit the diverse themes they explored, from social criticism to historical narrative. Poets like Tennyson employed rich, descriptive language and classical references to convey deeper meanings.

Meter in Poetry

The Romantics debated the use of meter, with Wordsworth advocating for simple forms that reflected the rhythms of natural speech, while others, like Coleridge, defended the use of more traditional meters to achieve specific poetic effects. Victorian poets often experimented with a meter to achieve various effects. For example, Gerard Manley Hopkins developed “sprung rhythm,” which broke away from traditional metrical patterns to more closely mimic natural speech rhythms, reflecting the complexity and dynamism of Victorian thought.

Fancy and Imagination

Coleridge distinguished between Fancy and Imagination in his critical works. He saw “fancy” as a mechanical process that rearranges existing ideas, while “primary imagination” is the spontaneous, creative force that perceives and brings new insights into reality. “Secondary imagination” involves the conscious effort of the poet to re-create and transform these insights into artistic expression. While influenced by Romantic ideas, Victorian poets often took a more pragmatic approach. They engaged with imagination but focused on its application to societal and moral themes rather than purely creative or abstract ends.

Willing Suspension of Disbelief

Coleridge introduced this concept, which refers to the reader’s willingness to accept the implausible or fantastic elements in a literary work to enjoy the story. For the Romantics, this was vital in creating a space where imagination could explore beyond the boundaries of reality. While Victorian poets and writers utilised this concept, they often combined it with realism and social criticism, encouraging readers to reflect on the deeper truths or moral lessons within the narrative, even when encountering fantastic elements.

Poetry as Criticism of Life

The Romantics were less concerned with “criticism of life” and more focused on the emotional and imaginative aspects of poetry. However, they did implicitly critique life through their emphasis on individual freedom, nature, and emotional truth. Matthew Arnold famously argued that poetry should serve as a “criticism of life,” meaning it should reflect the moral and ethical challenges of the human experience. Victorian poets aimed to address social injustices, personal dilemmas, and the search for faith and meaning in a rapidly changing world.

Historical Fallacy

Historical fallacy refers to the misinterpretation of literary works by placing too much emphasis on the historical context of the author. Both Romantic and Victorian critics often challenged this fallacy, arguing for a focus on the universal and timeless elements of literature rather than solely its historical circumstances.

Personal Fallacy

The personal fallacy involves interpreting a literary work based solely on the author’s life or experiences. Romantic poets emphasised personal emotion and experience but warned against reducing work to mere autobiography. Victorian critics like Arnold sought to maintain a balance, acknowledging personal influences while highlighting the broader moral or social implications of literature.

Touchstone Method

Introduced by Matthew Arnold, the Touchstone Method involved comparing a literary work to passages from the great works of the past to evaluate its quality. Arnold sought to establish a standard for literary criticism based on the excellence of classical literature.

Critical Faculty and Creative Faculty

For the Romantics, the creative faculty (imagination) was supreme, and the critical faculty (reason and analysis) was secondary. They believed that true poetry emerged from an inspired state beyond the reach of mere rational thought. While the Victorians also valued creativity, they emphasised the critical faculty more, seeing it as essential for producing meaningful and socially relevant art.

Art for Life’s Sake

Art for life’s sake, reflects the belief that art should serve a moral or social purpose. Victorian poets and writers often sought to address social issues, reflect human experiences, and improve society through their works.

Art for Art’s Sake

Art for art’s sake, emerged in the late Victorian period, representing a reaction against the utilitarian view of art. Advocates like Oscar Wilde argued that art should be appreciated for its beauty and form without regard to moral or social function.

Key Differences and Transitions

- The Romantic period emphasised individual emotion and imagination, while the Victorian era shifted towards social responsibility in literature.

- Romantics often focused on nature and the supernatural, while Victorians grappled more with industrialisation and social issues.

- The spontaneity valued by Romantics gave way to more structured and moralistic approaches in the Victorian era.

- While Romantics often rejected rigid forms, Victorians saw a return to more structured poetic forms and novels.

- The Romantic focus on the individual transitioned to a more significant concern with society and social norms in the Victorian period.

- The debate between “Art for Art’s Sake” and “Art for Life’s Sake” became more pronounced in the Victorian era, reflecting broader social and philosophical changes.

Romantic and Victorian literature share connections but also diverge in critical ways. The Romantics focused on the imagination, emotion, and the individual’s inner experience, while the Victorians balanced these ideals with a strong sense of moral duty, realism, and social critique. In many ways, the Victorian period responded to and developed ideas initiated in the Romantic era, adapting them to a rapidly changing social and industrial landscape.