Generative grammar, a very formal system, is the first of the three models for describing the language discussed by linguist Noam Chomsky in Syntactic Structures. In linguistics, generative grammar is grammar (the set of language rules) that indicates the structure and interpretation of sentences that native speakers accept as belonging to their language. Adopting the term ‘generative’ from mathematics, Chomsky introduced the concept of generative grammar in the 1950s. This theory is also known as transformational grammar, a term still used today.

- Generative grammar is a theory of grammar developed by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s. It is based on the idea that all humans have an innate language capacity.

- Linguists who study generative grammar are not interested in prescriptive rules but in uncovering the foundational principles that guide all language production.

- Generative grammar accepts as a basic premise that native speakers of a language will find specific sentences grammatical or ungrammatical and that these judgments give insight into the rules governing the use of that language.

Grammar refers to the rules that structure a language, including syntax (the arrangement of words to form phrases and sentences) and morphology (the study of words and how they are formed). Generative grammar is a theory of grammar that holds that human language is shaped by a set of fundamental principles that are part of the human brain (and even present in the brains of small children). This “universal grammar,” according to linguists like Chomsky, comes from our innate language faculty.

Generative vs. Prescriptive Grammar

Generative grammar is distinct from other grammar, such as prescriptive grammar, which attempts to establish standardised language rules that deem specific usages “right” or “wrong,” and descriptive grammar, which attempts to describe language as it is used (including the study of pidgins and dialects). Instead, generative grammar attempts to get at something more profound—the foundational principles that make language possible across all humanity.

For example, a prescriptive grammarian may study how parts of speech are ordered in English sentences to lay out rules (nouns precede verbs in simple sentences, for example). However, a linguist studying generative grammar is more likely to be interested in issues such as how nouns are distinguished from verbs across multiple languages.

Principles of Generative Grammar

The main principle of generative grammar is that all humans are born with an innate capacity for language and that this capacity shapes the rules for what is considered “correct” grammar in a language. The idea of a natural language capacity—or a “universal grammar”—is not accepted by all linguists. Some believe, to the contrary, that all languages are learned and, therefore, based on certain constraints.

The universal grammar argument proponents believe that children are not exposed to enough linguistic information to learn grammar rules when they are young. According to some linguists, children knowing grammar rules is proof that an innate language capacity allows them to overcome the “poverty of the stimulus.”

Examples of Generative Grammar

As generative grammar is a “theory of competence,” one way to test its validity is with what is called a grammaticality judgement task. This involves presenting a native speaker with a series of sentences and having them decide whether the sentences are grammatical (acceptable) or ungrammatical (unacceptable).

E.g., 1. The man is happy. 2. Happy man is the.

Here, a native speaker would judge the first sentence as acceptable and the second as unacceptable.

Language is described by a particular grammar as the set of all the sentences it generates. The set of sentences may be, in principle, either finite or infinite in number. But English comprises an unlimited number of sentences because there are sentences and phrases in the language that can be extended indefinitely and will be accepted as perfectly usual by native speakers. But the point is that no definite limit can be set to the length of English sentences. Therefore, it is to be accepted that, in theory, the number of grammatical sentences in the language is infinite.

However, the number of words in the English vocabulary is assumed to be finite. There is a considerable variation in the words known to different native speakers, and there may well be some difference between every individual’s active and passive vocabulary. Indeed, neither the active nor the passive vocabulary of any native speaker of English is fixed and static, even for relatively short periods.

Sentences can be represented at two levels: at the syntactic level as a sequence of words and at the phonological level as the sequence of phonemes. Following Chomsky, it can be said that every different sequence of words is a different sentence. Under this definition, not only are The dog bit the man and The man bit the dog are different sentences, but so also are I had an idea on my way home and On my way home I had an idea. From the purely syntactic point of view, the phonological structure of words is irrelevant, and we could represent them in various ways.

Terminal and Auxiliary Elements

Terminal elements occur in sentences: words at the syntactic level and phonemes at the phonological level. All other terms and symbols employed in formulating grammatical rules may be described as auxiliary elements.

In generative grammar, the fact that a particular word belongs to a specific class must be made explicit within the grammar. In effect, this means, in the grammar of the type formalised by Chomsky, that every word in the vocabulary must be assigned to the syntactic class or classes to which it belongs and not leave it to the person referring to grammar to decide whether a particular word satisfies the definition or not.

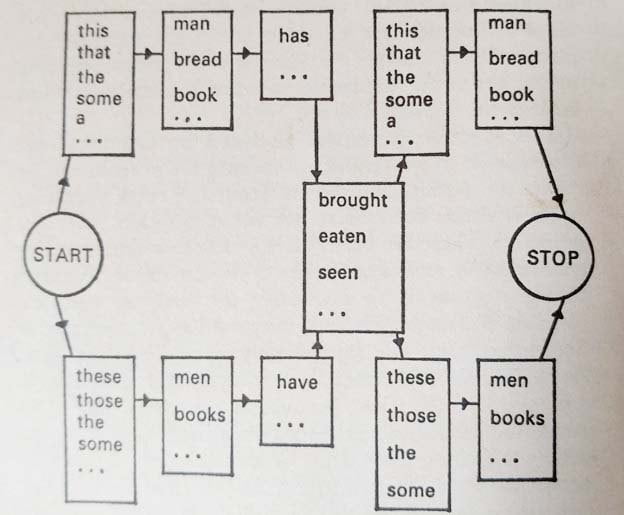

The simplest grammars discussed by Chomsky that are capable of generating an infinite number of sentences using a finite number of recursive rules operating upon a finite vocabulary are what he calls finite-state grammars. These are based on the view that sentences are generated using a series of choices made from left to right: that is to say, after the first, or leftmost, element has been selected, every subsequent choice is determined by the immediately preceding elements. One way of representing graphically what has just been said in words is using the ‘state diagram’.

We can think of grammar as a machine or device that moves through a finite number of initial states (start) as it passes from the initial state(start) to the final stage(stop) in the generation of sentences.

Chomsky’s proof of the inadequacy of finite-state grammar rests upon the fact that there may be dependencies between non-adjacent words and that these interdependent words may be separated by a phrase or clause containing another pair of non-adjacent interdependent words. For example, in a sentence like Anyone who says that is lying, there is a dependency between the words anyone and is lying. They are separated by the simple clause who says that (in which there is a dependency between who and says).

E.g., Anyone who says that people who deny that…are wrong is foolish.

The result is a sentence with ‘mirror image properties’, that is to say, a sentence of the form a+b+c…x+y+ z, where there is a relationship of compatibility or dependency between the outermost constituents (a and z) between the next outermost (b and y) and so on. Any language that contains an indefinitely large number of sentences with such ‘mirror image properties’ is beyond the scope of finite-state grammar.