Folklore refers to the traditional knowledge, beliefs, and cultural expressions that have been orally transmitted across generations. It encompasses a wide range of forms such as folk songs, folktales, folk dances, rituals, artefacts, and social institutions. These elements collectively preserve the wisdom, values, and customs of a community, providing insight into their way of life. Folktales are often presented in verse and are linked to fertility cults or seasonal rituals, while folk songs such as Payyannur Pattu narrate local histories through music and storytelling. Beneath their rhythmic surface, these oral compositions carry deeper meanings about social relations, labour, ecology, and morality. Thus, folklore is not merely a form of entertainment but a dynamic mode of transmitting cultural knowledge across generations.

- Definition: Folklore refers to the traditional knowledge, beliefs, and cultural expressions transmitted orally across generations.

- It includes folk songs, folktales, folk dances, rituals, artefacts, and institutions.

- Folklore preserves the collective wisdom of communities and conveys knowledge about local customs, values, and ways of life.

- Folktales are often narrated in verse form and linked to fertility cults, rituals, and seasonal celebrations.

- Works like Payyannur Pattu serve as narratives of local history, combining musical rhythm with storytelling.

- Beneath their surface narratives, folklore preserves layers of cultural and social knowledge—about labour, ecology, kinship, and morality.

Folklore as Social Knowledge

The knowledge preserved within folklore should not be viewed as individual belief but as a collective, social understanding rooted in community life. Each oral tradition arises from a specific cultural and ecological setting, reflecting the realities of the people who created it. Although this knowledge is situational and localised, it should not be excluded from the broader category of knowledge. Recognising folklore as a legitimate form of knowledge means appreciating its embeddedness within everyday life and its capacity to reveal the values and worldviews of a society.

- The knowledge embedded in folklore is not individual but collective and social.

- It reflects situational realities and the specific cultural contexts in which it originates.

- Oral traditions embody community knowledge systems, shaped by locality, ecology, and social structure.

- Recognising folklore as knowledge means accepting that it is contextual and dynamic, rather than fixed or universal.

Theyyam and the Thottam Tradition

One of the most distinctive forms of folklore in Kerala is the ritual performance of Theyyam, particularly prominent in the northern districts. Theyyam is a form of ancestral and deity worship accompanied by a body of oral narratives known as Thottam. Each Theyyam has a specific Thottam that recounts the origin, attributes, and deeds of the deity being invoked. Thottams typically consist of several parts, including invocations, songs of praise, mythic narration, and blessings for prosperity. Although they may have originated from individual compositions, Thottams are better understood as the collective creations of communities, transmitted and refined over generations. They are repositories of local knowledge, containing information about cosmology, hunting practices, paddy cultivation, kinship systems, and social values such as equality, justice, and cooperation.

- Theyyam is a ritual performance from north Kerala, worshipping ancestors and local deities.

- The Thottam is the oral narrative (song) that accompanies and explains each Theyyam ritual.

- Every Theyyam has a specific Thottam, usually composed of several parts:

- Invocation of the deity.

- Praise and mythic description.

- Prayers for prosperity.

- Thottams were likely composed collectively and evolved over generations, reflecting communal authorship.

- They are repositories of knowledge—containing insights into cosmology, agriculture, hunting, social values, and kinship systems.

Pottan Theyyam: Knowledge and Egalitarianism

Among the many Theyyams performed in Malabar, Pottan Theyyam holds particular importance for its philosophical and social message. The myth centres on a dialogue between Pottan, a Pulaya labourer representing simplicity and marginalised existence, and Shankaracharya, the symbol of Brahminical intellect. When Shankaracharya instructs Pottan to move aside to avoid ‘polluting’ him, Pottan questions the logic of such discrimination by asking where he could move if all space belongs to the divine. He further argues that the colour of blood is the same in both the Brahmin and the Pulaya, thus invalidating caste hierarchies. Pottan’s discourse dismantles the artificial division between theory and labour, asserting that practical labour is itself a form of knowledge. His reasoning promotes egalitarianism and inclusivity, rejecting the rigid stratification of knowledge and power. Through this symbolic exchange, Pottan Theyyam becomes a vehicle of social critique, voicing the wisdom of the oppressed and envisioning a more just social order.

- Among the many Theyyams, Pottan Theyyam holds special significance for its philosophical and social message.

- The myth centres on a dialogue between Pottan, representing a Pulaya labourer (symbol of simplicity), and Shankaracharya, symbolising Brahminical intellect.

- When Shankaracharya asks the Pulaya to move aside to avoid ‘pollution’, Pottan questions:

- Where should we move if all space is divine?

- Why divide people when the colour of blood is the same for all?

- The dialogue challenges caste hierarchy and the false division between theory and labour.

- Pottan argues that knowledge gained through labour is as valuable as theoretical learning.

- His reasoning asserts egalitarianism, rejecting social stratification and advocating inclusive knowledge systems.

- The myth symbolically critiques medieval Kerala’s caste order, where Pulayas were enslaved agricultural workers.

- Through Pottan’s voice, folklore becomes a vehicle for social critique, articulating the wisdom of the marginalised.

Folklore as Counter-History

This dialogue acquires deeper meaning when viewed in its historical context. During medieval Kerala, Brahmin scholars like Shankaracharya produced systems of knowledge that legitimised caste hierarchies, while Pulayas were enslaved agricultural workers who sustained the economy. In the Thottam-pattu of Pottan Theyyam, this context is reinterpreted symbolically to represent the resistance and awareness of the marginalised. The myth challenges not only the hierarchical structure of traditional Kerala but also the colonial and Orientalist constructions that portrayed Eastern societies as inherently hierarchical. In doing so, folklore emerges as a counter-history—a medium through which marginalised groups articulate alternative visions of society and justice.

- The Thottam of Pottan Theyyam represents a form of people’s knowledge that contests elite narratives of society.

- It questions the Orientalist notion that Eastern societies were inherently hierarchical while Western societies were egalitarian.

- Folklore thus becomes a source of alternate historiography, offering insight into values, resistance, and equality in Kerala’s social past.

Kathivanoor Veeran: Folklore and Individualism

Another significant example of folklore as a social text is the Thottam of Kathivanoor Veeran, which highlights the theme of individualism. The story narrates the life of Mannappan, a Thiyya man who defies caste expectations by refusing to follow his community’s traditional occupation. He moves to Coorg, becomes an oil trader, and achieves economic independence through resilience and hard work. By marrying a woman from a lower caste, he asserts his autonomy and challenges social conventions. Mannappan’s eventual deification as Kathivanoor Veeran Theyyam symbolises the recognition of personal freedom and rational choice—values that mark the transition from a collective, hierarchical order to a more modern individual consciousness. The eighteenth century, during which this myth likely took shape, was a period of social transformation in Malabar, and Kathivanoor Veeran’s story reflects these evolving attitudes. Even today, devotees invoke his blessings for success in legal matters, business ventures, and the safe return of migrant workers, demonstrating how folklore continues to shape modern experiences and aspirations.

- The Thottam of Kathivanoor Veeran presents the story of Mannappan, a Thiyya man who rejects traditional caste occupations.

- Mannappan chooses an independent path—becoming an oil trader in Coorg—defying his community’s expectations.

- His success and marriage across caste boundaries symbolise personal autonomy and rational choice, ideas rare in pre-modern Kerala.

- After dying heroically in battle, he is deified as Kathivanoor Veeran Theyyam, worshipped for courage and justice.

- The myth belongs to the eighteenth century, a transitional era when Kerala was shifting from a collective social order to modern individual consciousness.

- The continued worship of Kathivanoor Veeran, even in contemporary contexts (e.g., prayers for migrant safety or legal victories), reflects the modern relevance of individuality and justice.

- Folklore here functions as a medium of social transformation, introducing modern values like individual freedom through traditional forms.

Folklore as Historical Knowledge

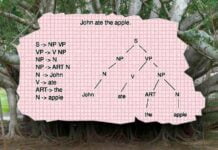

Beyond these examples, folklore in Kerala also functions as a form of historical knowledge, often referred to as mnemonic history. Unlike Western historiography, which values empirical evidence and linear causality, mnemonic history relies on collective memory expressed through ritual, song, and performance. These oral traditions preserve the experiential truths of communities, especially those excluded from written history. The Thottam songs of Payyanur in Kannur, for instance, provide a counter-narrative to the Brahminical myth of Kerala’s origin, which claims that Parasurama reclaimed the land from the sea and gifted it to Brahmins. The Thottam corpus reveals instead that Pulaya labourers were forcibly brought to construct the Payyanur Subrahmanya Temple, denied wages, and later excluded from the temple they built.

- Folklore can serve as a historical record—what scholars call mnemonic history.

- Unlike Western historiography, which depends on empirical evidence and linear narrative, mnemonic history transmits collective memory through ritual and song.

- Oral traditions preserve experiential truths rather than factual chronology.

- Such histories reflect the lived experiences of marginalised communities and their relationship with power and place.

Mnemonic History in Thottam Narratives

Within these narratives, figures such as Arayil Chirutha and her son Virunthan emerge as powerful symbols of resistance and suffering. Chirutha, a Pulaya woman who entered the temple and was expelled for ‘pollution’, was later deified as Arayil Bhagavathi. Her son Virunthan defended the temple from invaders but was betrayed and killed by the upper castes, who later deified him to remove their curse. The ritual enactment of Virunthan Theyyam continues to this day, performed exclusively by the Pulaya community of Payyanur. During the all-night ritual, the community gathers to sing the Thottam and re-enact their ancestors’ experiences. This performance serves as both remembrance and renewal—preserving history through embodied ritual and shared memory. These Thottams serve as mnemonic commitments—songs and rituals ensuring that the experiences of the oppressed are remembered and passed on.

- A corpus of Thottam songs from Payyanur (Kannur district) provides a counter-narrative to the Brahminical myth of Kerala’s origin.

- The traditional myth says Kerala was reclaimed from the sea by Parasurama and donated to Brahmins, erasing pre-existing inhabitants.

- The Thottam corpus tells a different story:

- Pulaya labourers were forcibly brought to build the Payyanur Subrahmanya Temple.

- After construction, they were denied wages and excluded from the temple.

- A Pulaya girl, Arayil Chirutha, entered the temple and was expelled for ‘polluting’ it; she was later deified as Arayil Bhagavathi.

- Her son, Virunthan, later defended the temple against invaders but was betrayed and killed by the upper castes.

- The Brahmins, cursed with madness, were forced to deify Virunthan and establish his Theyyam cult.

- The rituals surrounding Virunthan’s Theyyam are collective performances of memory, retelling the suffering and resistance of Pulaya labourers.

Redefining Knowledge and History

In such rituals, memory itself becomes a form of history. Before the rise of modern Enlightenment rationality, memory was considered a legitimate way of knowing the past. However, Western historical thought later dismissed memory as subjective and unscientific, privileging documentary evidence instead. This shift marginalised the historical consciousness of non-literate societies. As scholars such as Velcheru Narayana Rao, David Shulman, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam observe, each culture writes history through its own modes of expression, and dominant cultures often deny historicity to the communities they subjugate. Folklore and ritual, therefore, serve as alternative ways of recording history, allowing marginalised groups to reclaim their past and assert their identity through performative acts.

- Folklore challenges Western Enlightenment notions of objective history and empirical truth.

- It demonstrates that memory and subjectivity can also be valid forms of knowledge.

- Knowledge should not be measured by universality but understood as situational and cultural.

- Every society constructs history using its own literary and performative practices.

- As scholars like Velcheru Narayana Rao, David Shulman, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam argue, dominant cultures often deny history to marginalised ones.

- Folklore, therefore, is a mode of resistance—a way for the marginalised to write their own history and preserve their worldview.

Significance of Folklore in Knowledge Systems

From this perspective, folklore is not merely a reflection of culture but a creative form of knowledge production. It encodes philosophical, ethical, and social principles, challenges dominant ideologies, and preserves the collective memories of resistance. Myths like Pottan Theyyam and Kathivanoor Veeran articulate ideas of equality and individuality, while Thottam songs, such as those of Virunthan, record the lived realities of the oppressed. These narratives form a parallel historiography—one rooted in memory, performance, and oral tradition. Through its fusion of art, ritual, and social consciousness, folklore stands as a living archive of Kerala’s cultural evolution, embodying both its historical depth and its ongoing struggle for justice and self-definition.

- Folklore is not just art or entertainment—it is a knowledge system rooted in lived experience.

- It reveals how rituals, songs, and oral narratives encode philosophical, ethical, and social principles.

- It preserves alternative histories, celebrates collective memory, and challenges dominant ideologies.

- Folklore ensures that knowledge of the oppressed survives, even when denied by mainstream historical discourse.