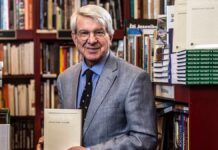

Aboriginal Australia, also known by its first line, To the Others, appears in Noongar playwright and poet Jack Davis’s poetry collection Jagardoo: Poems from Aboriginal Australia (1977). Davis, one of the most influential Aboriginal poets and playwrights of the 20th century, uses his poetry to speak on behalf of Indigenous Australians whose voices have been historically silenced.

Aboriginal Australia is a searing indictment of the violence, betrayal, and dispossession endured by Aboriginal people under colonial rule. European colonisers clad with military power sacked the peaceful lives of the indigenous people and denied them their birthright, their land, and their freedom. Those who came in their way were either eliminated or oppressed. In this poem, Davis details several brutish events occurring in Australia, starting from the settlement of colonisers till the day of writing this poem in the 20th century. Davis confronts the mythology of national pride and exposes the brutal reality of Australia’s colonial past and its continuing legacy.

The poem opens with a direct, accusatory address to non-Indigenous Australians—those who initially presented themselves as kin, only to betray the Indigenous people. Davis recounts how these “brothers” “swamped my way of gladness,“ stole children, and denied pleas for justice—referencing specific incidents like loss at Yirrkala and massacres at places such as Lake George hills, where “thin stick bones of people“ remain.

He mourns the wiping out of entire tribes —Warrarra, Murray—highlighting their erasure “without a trace.“ The poem details violence: rape, gun, mass graves; and systemic abuse: “disease and lordly rape“ backed by religious indoctrination and bureaucratic oppression (“Christ, red tape, tobacco, grog and fears”)—all part of the “brutish years“ inflicted by settlers.

In the closing lines, Davis condemns the colonisers’ self-justifications and nationalistic pride, declaring instead that the true history is one of Indigenous “crucifixion“ and ongoing trauma:

“Now you primly say you’re justified,

And sing of a nation’s glory,

But I think of a people crucified –

The real Australian story.”

Summary

The poem is structured as a direct address to white Australians— “the others“ —who, under the guise of kinship and civilisation, perpetrated acts of theft, murder, and cultural erasure. The speaker begins by stating that he was told he was a brother, but instead of solidarity, he received destruction: “you swamped my way of gladness.“ The tone from the outset is accusatory and mournful.

The speaker recounts atrocities such as massacres at places like Lake George and the forced removals of children—a clear reference to the Stolen Generations. Davis uses the metaphor of being buried deep in bureaucratic and spiritual debris—”Christ, red tape, tobacco, grog and fears”—to express how Indigenous people have been overwhelmed not just by physical force, but by systemic and institutional oppression.

The poem mourns the loss of entire Aboriginal groups, such as the Warrarra and Murray tribes, communities now erased “without a trace.“ The speaker refers to personal and collective suffering, aligning himself with generations of Aboriginal people whose stories have been left out of dominant historical narratives.

In the final stanza, Davis juxtaposes the settler narrative of national glory with the Indigenous experience of crucifixion. The poem ends with a powerful reversal: “But I think of a people crucified – / The real Australian story.”

Themes

Betrayal and “Othering”

The poem opens with apparent brotherhood—”kin to one another”—that veils deeper deceit. Davis critiques this performative relationship, exposing it as calculated colonisation using “guile“ to gain trust before domination ensued. This rhetorical strategy confronts the reader with the rhetorical and moral violence embedded in colonisation narratives.

Genocide and Cultural Erasure

Image after image underscores genocide—massacres, “thin stick bones,“ and evaporation of entire communities. Repetition of loss (“I cry again… I mourned again…”) emphasises collective trauma and the cyclical remembrance of tragedies spanning diverse tribal groups.

Systematic Abuse and Colonial Power

Davis exposes the interconnected mechanisms of control: religious, legal, medical, military, and sexual. He demonstrates that colonisation was not only violent but also insidious, embedding trauma in institutions such as mission churches and government bureaus.

Subversion of National Myth

By juxtaposing settler pride with Indigenous suffering, the poem deconstructs narratives of national glory, demanding that Australia reconcile with the “real Australian story.”

Theoretical Applications

Postcolonial Criticism

Davis rejects settler-colonial narratives by re-centering Indigenous experience. His poem is emblematic of Indigenous counter-history—recovering voices erased from official history and exposing the cultural silencing executed by colonial power.

Feminist and Gendered Readings

While not overtly gendered, the poem’s mention of “lordly rape“ invokes a history of sexual violence against Aboriginal women—a key issue in feminist and intersectional postcolonial critiques.

Trauma Theory

The speaker’s repeated mourning and vivid imagery evoke ongoing intergenerational trauma. This is communal mourning—”I cry again,” “I mourned again”—demonstrating how colonial violence persists in memory and identity.

Oral Tradition and Testimony

Although written, the poem’s tone echoes Aboriginal oral practices. Its cadence and repetition give it a ritualistic, testimonial character: a spoken confession or public remembrance meant to bear witness and pass on collective memory.

Tone and Voice

The poem’s tone is one of grief, anger, and indictment. The use of direct address intensifies the confrontational nature of the poem as if the speaker is forcing the reader to witness and reckon with the history they may prefer to forget. Davis speaks in a collective voice, embodying the trauma of his people, making the poem a communal elegy.

Structure and Form

Davis writes in free verse, allowing the rhythm and cadence of his lines to resemble spoken testimony or oral lamentation. This reflects the oral storytelling traditions of Indigenous Australians and emphasises the poem’s function as witness and remembrance.

The lack of traditional stanzaic structure or rhyme mirrors the emotional chaos and disorder brought upon by colonisation. It resists aesthetic neatness, favouring a raw and unfiltered delivery.

Imagery and Language

Davis’s imagery is stark and visceral. The “thin stick bones of people“ evoke death and decay. The “red tape, tobacco, grog and fears“ is a loaded image summarising multiple tools of colonial control: legal systems, addictive substances, religious guilt, and psychological trauma.

His language is accessible yet emotionally charged, drawing on symbols of Christian martyrdom (“crucified”) and legal deception (“red tape”) to critique settler hypocrisy and justify Indigenous suffering.

Historical and Cultural Significance

The poem was written in a period (1970s) when Aboriginal activism was gaining momentum in Australia. Davis, a Noongar man, lived through much of the systemic racism he describes. This gives the poem documentary weight as well as literary power.

He names specific locations and groups to restore erased histories—this is a political act, not just a poetic expression. By naming these lost tribes, he re-inscribes them into Australia’s cultural memory.

Jack Davis’s “Aboriginal Australia“ is not only a poem but a testimonial document. It challenges settler Australians to confront the historical amnesia at the heart of their national identity. By blending personal grief with collective memory, Davis rewrites the official story of Australia to include the dispossessed, the massacred, and the silenced. His poem remains essential in Australian literature and postcolonial studies, offering a powerful reminder of the moral cost of empire and the resilience of the Indigenous voice.