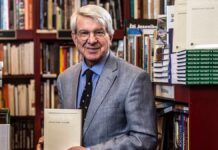

Prof Gopinath Ravindran, the former Vice Chancellor of the Kannur University, is a renowned history scholar. He has written prominent works that serve as a reference for students and scholars, and he is known for his work on historical demography and agrarian regimes.

The Indian Constitution: Limited but Necessary presents a nuanced exploration of the Indian Constitution, offering critical reflections on its role, strengths, and limitations. Prof Ravindran navigates through the complex fabric of India’s constitutional framework, emphasising its significance in shaping the nation’s democratic ethos while recognising its inherent constraints.

The Central Thesis

Prof Ravindran’s central thesis revolves around the idea that while the Indian Constitution is limited in scope and application, it remains an indispensable foundation for the country’s governance and legal framework. He argues that the Constitution, despite its limitations, is crucial in maintaining the delicate balance between various arms of the government and ensuring the protection of fundamental rights.

The Constitution is the foundational principle as far as any democracy is concerned. In a democratic system, it is the cornerstone upon which democracy is built. Prof Ravindran begins this essay by highlighting the significance of the Constitution. He is concerned about the fact that though the Indian Constitution is necessary, highlighting the role it has played in building present India, it has limitations as far as the redistributive justice to millions of people living in poverty and facing discrimination is concerned.

He states that the Constitution serves as a legal foundation for the nation and sets forth the objectives and values of the state and the relationship between the different elements of the state, including the people. In addition, he analyses the strengths of the Constitution and the need to uphold the spirit of the Constitution to guarantee decent living conditions for all sections of people irrespective of any barrier, economic, political, communal or territorial.

Prof Ravindran speaks about the specialities of our Constitution. They are:

- Indian Constitution was drafted over nearly three years by an elected Constituent Assembly. The Constituent Assembly was formed on 6th December 1946 and met on 9th December 1946 for the first time, from which a seven-member committee headed by Dr B R Ambedkar had been formed to draft the Constitution.

- It is the longest-written Constitution in the world. It is running into about 1,40,000 words. It had 22 parts, 395 articles and eight schedules. Now, it has 25 parts, 470 articles and 12 schedules.

- It invokes the people of India as the source of the Constitution, unmediated by any God or religion.

The Constituent Assembly

There were 389 members in the Constituent Assembly, of which 292 represented the provincial legislatures that came into being in 1946. 93 were the representatives of the Princely States, and four were from the chief commissioner provinces of Delhi, Ajmer-Merwara, Coorg and British Baluchistan. After 1947, after the partition, a section of the members left. After June 1947, the Constituent Assembly had only 299 members.

Strength of the Constitution

Our Constitution has the potential to anticipate the changes that are needed in future. We have provisions for amendments. But these amendments cannot be made easily. There are rigorous procedures for these amendments. A simple majority in Parliament can pass some of these amendments. For some other amendments, a special majority is needed in both houses of the Parliament. In some other cases, a special majority in both houses and a particular number of state assemblies are also required.

Kesavananda Bharati vs. the State of Kerala Case

Kesavananda Bharati case judgement is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of India that outlined the fundamental structure doctrine of the Indian Constitution. The case is also known as the Fundamental Rights Case. The court asserted its right to strike down amendments to the Constitution that violated the fundamental architecture of the Constitution. Kesavananda Bharati was an Indian Hindu monk who served as the Shankaracharya (head) of Edneer Mutt, a Hindu monastery in Kasaragod district, Kerala. He filed a case against the Land Reform Bill of the Government of Kerala when there was an attempt to annex the territory belonging to his institution. In 1973, 13 members of the constitution bench of the Supreme Court of India made a landmark judgment that the Parliament could not amend the basic structure of the Constitution. It was a historic judgment that upheld the spirit of the Constitution.

Another amendment Prof Ravindran discusses in the essay is the 42nd amendment, which effected changes in almost all sections of the Constitution. It was passed when an internal emergency was operational in India. It was for the first time that the preamble of the Constitution was amended. It became controversial because it gave the Prime Minister and the Parliament power beyond the judicial review. The amends were in the line of making the Parliament and Executives stronger and the Judiciary weaker. The Janatha Party Government, which came into power in 1977, repealed most of the amendments by subsequent amendments in 1977 and 1978. The essay says that our Constitution, so far, has been able to withstand the pressures even when there was a massive majority of seats for the ruling party. The fundamental structure doctrine came to the rescue of the Constitution.

Context of the Rescue of the Constitution

We had a long freedom struggle. For about 200 years, we fought in organised and unorganised ways against the imperial forces. Different sections of Indian society took different positions concerning the nationalist movements. The British easily defeated the members of the ancient regimes. They took sides with the British. Feudal Lords and a section of the religious nationalists also supported British imperialism. The liberals and the leftists primarily led the long-drawn struggle for Indian Independence. The Congress Party carried them, and later the Congress Socialist Party. They had this struggle zealously forward. Though India got freedom, there was no structural change, so the lion part of the Indian population is living in poverty and discrimination even now. There was no redistribution of wealth and property. They accumulated in very few hands, and poor people remained poor.

Another point he discusses is that the Constitution is the legal embodiment of our national leaders’ values, aspirations, and anxieties. They sacrificed their comforts to build a free and democratic India when framing the Constitution; they had to bring everybody confidence in building a nation. It was a huge task for the administrators to take India to progress. So, support from all sections of society was needed. All of their interests had to be considered. An outright revolutionary transformation would not be possible. That would do more harm.

Formation of the Constituent Assembly

The speaker goes back to history to point out our demands for democracy. There were very organised demands for democracy from the early 20th century onwards. In 1927, The Indian Statutory Commission (Simon Commission), a group of seven Members of Parliament under the chairmanship of Sir John Simon, was sent by the British to review the situation in India and report on India’s constitutional progress for introducing constitutional reforms as promised in 1919. Many Indians strongly opposed the Commission. It was opposed by Nehru, Gandhi, Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the Indian National Congress because it contained seven members of the British Parliament but no Indians—instead, we set up a commission headed by Motilal Nehru in 1928 to determine the principles of our Constitution. In 1938, during the civil disobedience movements, the Congress Party repeatedly demanded a Constitution for India, which was drafted by the Indians, not by the British. In 1935, the Government of India Act was passed. It gave autonomy to the provinces, and the provincial legislatures were formed. In 1942, the British sent the Cripps Mission to India. They agreed that the Indians would ultimately prepare the Indian Constitution. After the Second World War, the Labour Party Government under Clement Attlee assumed charge in England. In 1946, the Cabinet Mission planned and recommended the Constituent Assembly of India, which came into being in December 1946.

Nehru called the constituent assembly “a nation on the move”. It had to understand the aspirations of the people. Prof Ravindran says that the fundamental structure doctrine ensures India is a sovereign, socialist, secular democratic republic and a welfare state based on directive principles and a robust federal system. It has been successful in maintaining the unity and integrity of the country. We have to give special care to safeguard the religious minorities and the interests of the people from different territories. He refers to many communal riots unleashed in India in the past years. He reiterates that the Constitution has successfully ensured political democracy and secularism. But he adds it could perform only a limited role in redistributive justice to millions living in poverty. He quotes Ambedkar, “Parliamentary democracy in India developed a passion for liberty, but unfortunately, this passion for liberty swallowed the commitment to equality”.

Prof Ravindran reiterates that though the Constitution could perform only a limited role in ensuring redistributive justice to millions of people living desperately in poverty, it has, till now, protected our democratic rights and the country’s secular fabric. He praises the Constitution for laying down a foundation for a democratic India, accommodating changes that are likely to happen, providing room for amendments, and, at the same time, putting in check for amending the basic structure of the Constitution.

In the concluding part of the essay, Prof Ravindran asks us to be vigilant against any attempt to alter the basic structure and the directive principles, whether in the name of religion, nationalism, or economic efficiency. As responsible citizens of this democratic country, we must ensure that the spirit of the Constitution is upheld. He highlights that the spirit of the Constitution should reign supreme in a democratic country at any cost.

The Constitution as a Living Document

One of the critical strengths of Prof Ravindran’s analysis is his understanding of the Constitution as a living document. He acknowledges that the Constitution is not static but is continuously shaped by judicial interpretations, legislative actions, and societal changes. This dynamic nature, he argues, is what makes the Constitution both limited and necessary, as it must constantly adapt to serve the evolving needs of the nation.

Reflection on Democratic Ideals

The author’s reflection on the gap between democratic ideals and political realities is particularly poignant. He critiques how political expediency often undermines constitutional principles, leading to a disconnect between the ideals of justice, liberty, and equality and their implementation. Prof Ravindran’s sharp analysis here highlights the need for a more substantial commitment from all stakeholders—government, judiciary, and citizens alike—to uphold the Constitution’s values in practice.

Prof Gopinath Ravindran’s The Indian Constitution: Limited but Necessary is a profoundly reflective and insightful work that offers a balanced and critical appreciation of India’s constitutional framework. By recognising both the strengths and limitations of the Constitution, Ravindran provides a nuanced perspective that encourages readers to engage more deeply with the document. His work serves as a reminder that while the Constitution may have its flaws, it remains an essential pillar of India’s democracy, deserving of both critique and reverence.