The allomorphs are the variations of a morpheme that depend on the context in which they appear. An allomorph can be termed as a phonetic variant form of a morpheme. These tiny word-building blocks might seem insignificant, but they have a big impact on the way we form words and sentences. Sometimes morphemes change their sound or their spelling but not their meaning. Each of these different forms is classed as an allomorph, which is a different form of the same morpheme that is used in different contexts or positions.

For example, the plural morpheme ‘-s’ in English has three allomorphs: /s/, /z/, and /ɪz/, as in ‘cats’, ‘dogs’, and ‘buses’. Allomorphs can be used for grammatical tense and aspects. From irregular past tense verbs to plural nouns, allomorphs are all around us in the English language.

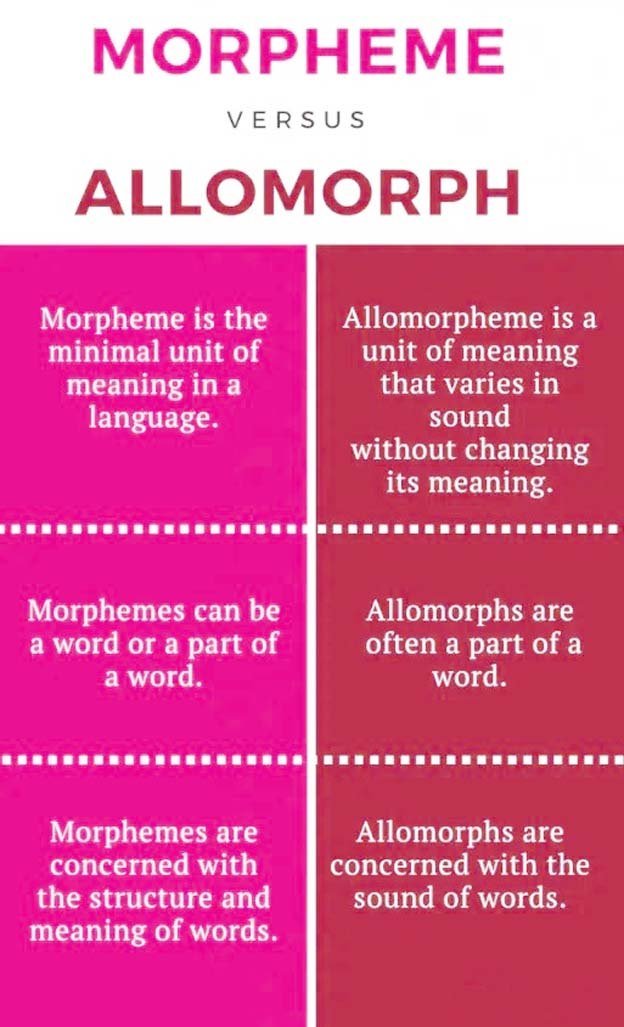

Morpheme and Allomorph

A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning in a language. This means that a morpheme cannot be reduced beyond its current state without losing its basic meaning. This makes it different from a syllable, which is a word unit -morphemes can have any number of syllables.

An allomorph is each alternative form of a morpheme. This could be a variation in sound i.e., pronunciation, or spelling, but never in function or meaning. Allomorphs are like the same morpheme wearing different disguises.

I bought an apple and a pear.

If we try to spot the allomorphs in this sentence, they are the indefinite articles ‘a’, and ‘an’. In the sentence above we see both allomorphs: ‘an’ for when the word following it begins with a vowel, and ‘a’ for when the word following the word starts with a consonant. Each form is spelt and pronounced differently, but the meaning is the same.

The three most common types of allomorphs in the English language:

- past tense allomorphs

- plural allomorphs

- negative allomorphs

Past Tense Allomorph

A past tense allomorph is a linguistic term used to describe different forms of the same morpheme, or grammatical unit, that express the past tense of a verb. In English, we add the morpheme ‘-ed’ to the end of regular verbs to show the action was completed in the past. For example, ‘planted’, ‘washed’, and ‘fixed’. Other examples of a past tense allomorph include ‘-d’ and ‘-t’ and they are used depending on the sound of the verb in its base form.

‘-ed’ always has the same function (making a verb past), but is pronounced slightly differently depending on the verb it is bound to. For example, in ‘washed’ it is pronounced as a /t/ sound (wash/t/), and in ‘planted’ it’s pronounced as a /ɪd/ sound (plant /ɪd/).

‘ed’ morpheme pronounced as /ɪd/

- wanted

- rented

- rested

- printed

‘ed’ morpheme pronounced as /t/

- touched

- fixed

- pressed

Each different pronunciation of the ‘ed’ morpheme is an allomorph, as it varies in sound, but not function.

Plural Allomorph

We typically add ‘s’ or ‘es’ to nouns to create their plural form. These plural forms always have the same function, but their sound changes depending on the noun.

The plural morpheme has three common allomorphs: /s/, /z/ and /ɪz/. Which one we use depends on the phoneme that precedes it.

When a noun ends in a voiceless consonant (ch, f, k, p, s, sh, t or th), the plural allomorph is spelt ‘-s’ or ‘-es’, and is pronounced as a /s/ sound. For example, books, chips, and churches.

When a noun ends in a voiced phoneme (b, d, g, j, l, m, n, ng, r, sz, th, v, w, y, z, and the vowel sounds a, e, i, o, u), the plural form spelling remains ‘-s’ or ‘-es’, but the allomorph sound changes to /z/. For example, bees, zoos, and dogs.

When a noun ends in a sibilant (s, ss, z), the sound of the allomorph sound becomes /ɪz/. For example, buses, glasses, and waltzes.

Other plural allomorphs include the ‘-en’ in words such as oxen, the ‘-ren’ in children, and the ‘-ae’ in words such as formulas and antennae. These are all plural allomorphs as they serve the same function as the more common ‘-s’ and ‘-es’ suffixes.

Negative Allomorph

Think of the prefixes we use to make a negative version of a word.

- informal (not formal)

- impossible (not possible)

- unbelievable (not believable)

- asymmetrical (not symmetrical)

The prefixes ‘-in’, ‘-im’, ‘-un’, and ‘-a’ all serve the same function but are spelt differently, therefore, they are allomorphs of the same morpheme.

Null Allomorph

A null allomorph, also known as a zero allomorph, zero morph, or zero bound morpheme has no visual or phonetic form – it is invisible! Some people even refer to null allomorphs as ‘ghost morphemes’. You can only tell where a null allomorph is by the context of the word.

Examples of null morphemes appear or rather, don’t appear in the plurals for ‘sheep’, ‘fish’ and ‘deer’. For example, ‘There are four sheep in the field’. We don’t say ‘sheeps’ – the plural morpheme is invisible, and so it is a null allomorph.

Other examples of null morphemes are in the past tense forms of words such as ‘cut’ and ‘hit’.